Nano-towers fire off single photons

Würzburg physicists are global leaders in the creation of sophisticated nanostructures. The fruits of their research could make tap-proof data transmission a possibility in the future.

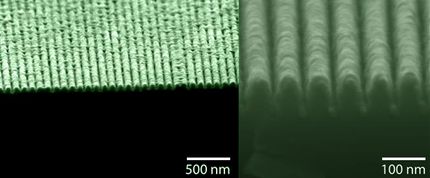

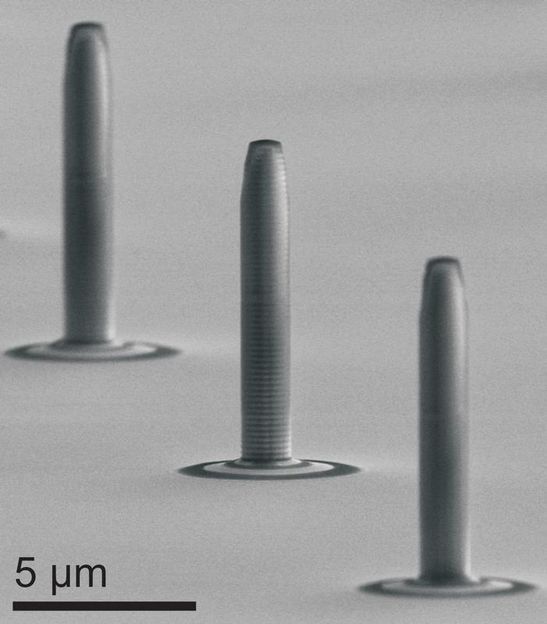

Tiny towers, a hundred times thinner than a human hair, with special properties:such nanostructures are produced by the Department of Applied Physics at the University of Würzburg.

Monika Emmerling / Adriana Wolf

At the heart of the concept are tiny towers, made from semiconducting material, at the University of Würzburg's Department of Applied Physics. They are around ten micrometers in height, with a diameter of just one to two micrometers - a human hair is roughly a hundred times thicker.

Contained inside the towers are special structures capable of emitting light: these are known as quantum dots, and their electronic and optical properties can be customized during production. Quantum dots, in the same way as single atoms, possess precisely defined energy states. This enables them to send out photons (light particles) with an exact amount of energy.

Single photons can be generated

What is special about the Würzburg quantum dot towers is that "with them it is possible to 'fire off' single photons in a targeted fashion. It is structural elements like these that are needed for the tap-proof transmission of data in the field of quantum cryptography," explains Würzburg physicist Stephan Reitzenstein.

However, to date, the production of single photons in these structures has only been achieved with temperatures well below minus 100 degrees Celsius. So, there are still hurdles to overcome before the concept can be routinely applied.

Thanks to the tiny towers developed in Würzburg, there are now new insights into quantum dots. Physicists on Professor Peter Michler's team (Institute of Semiconductor Optics and Functional Interfaces of the University of Stuttgart) have published these jointly with their Würzburg colleagues in the journal Nature Photonics.

Those involved in the publication from Würzburg's Department of Applied Physics were Stephan Reitzenstein, Andreas Löffler, Sven Höfling, and Professor Alfred Forchel. The Stuttgart team included Serkan Ates, Sven M. Ulrich, Ata Ulhaq, and Professor Peter Michler.

New tool for analyzing quantum dots

The Stuttgart physicists studied the Würzburg nano-towers as part of a venture sponsored by the German Research Foundation (DFG). "The towers serve as a new tool for analyzing the properties of quantum dots in a way never seen before," explains Reitzenstein.

The Stuttgart team discovered an unexpected effect, known as non-resonant coupling. This suggests strong light-matter interactions in such solid-state systems. According to Peter Michler, "this will have major repercussions on the design and functionality of future quantum emitters that are based on quantum dots."

Structure of the Würzburg towers

The new insights were made possible by the special structure and highly optimized production of the towers. The quality of the towers realized at the University of Würzburg is outstanding by global comparison.

The tiny structures consist of a sophisticated sequence of layers made from the semiconductors aluminum arsenide and gallium arsenide. "Their special structure makes them into high-quality optical resonators, which confine single photons on a light wavelength scale in all three spatial dimensions," says Stephan Reitzenstein.

Embedded in the center of the towers are some 100 quantum dots made from the semiconducting material indium gallium arsenide. Reitzenstein: "Using special spectroscopic procedures, however, a single quantum dot can purposefully be brought into resonance with the optical mode of a tower in order to conduct fundamental physics experiments on the interaction between light and matter."

Original publication: S. Ates et al.; "Non-resonant dot-cavity coupling and its potential for resonant single-quantum-dot spectroscopy"; Nature Photonics, published online on Nov. 22, 2009