Mass of the deuteron corrected

Sophisticated measurement technology for maximum precision

High-precision measurements of the mass of the deuteron, the nucleus of heavy hydrogen, provide new insights into the reliability of fundamental quantities in atomic and nuclear physics. This is reported in the journal "Nature" by a collaboration led by the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics Heidelberg, Germany, and partners from the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research Darmstadt and the Helmholtz Institute Mainz, Germany. Thus, data directly related to the atomic mass standard, are now available for hydrogen H, deuterium D and the molecule HD, which the scientists have also reweighed.

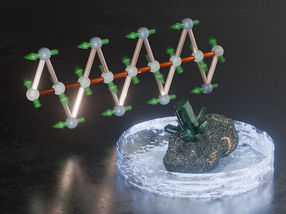

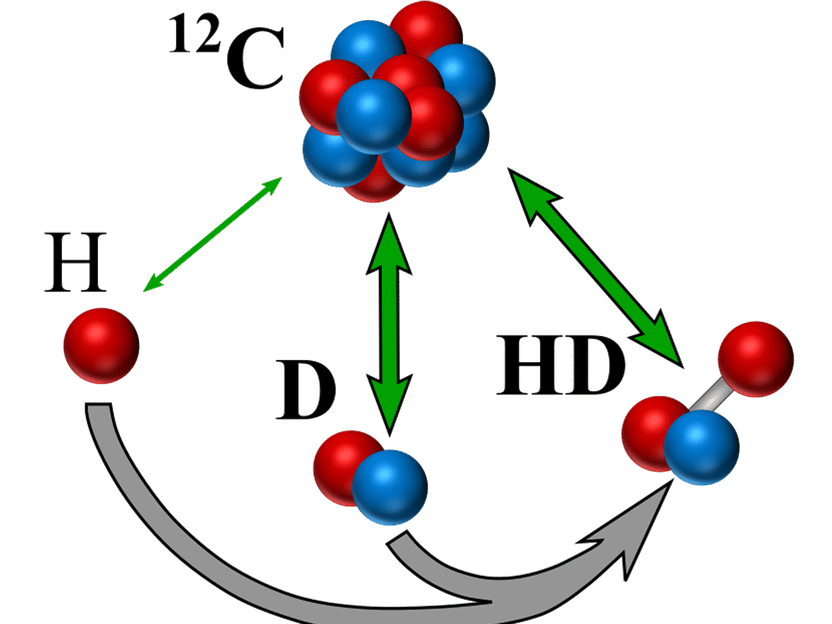

Directly against the atomic mass standard ¹²C measured hydrogen species (green arrows). The mass of HD may also be calculated from the masses of H and D together with the binding energy (grey arrow).

© MPIK

The masses of both atomic nuclei and electrons influence numerous properties of atoms and molecules, for example their spectra, i.e., which light colours they absorb or emit. Physicists like values of these masses to be as accurate as possible, because only with their knowledge precise calculations using atomic physics are possible for these spectra. Calculations are then confronted to direct measurements, which, for example, allows drawing conclusions about the reliability of basic physical theories.

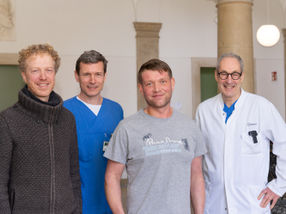

Hydrogen and its isotopes are of particular interest in this context, because their simple electron shell with only a single electron allows extremely precise calculations and thus very sensitive tests of fundamental physical theories. Furthermore, the mass of the deuteron can also be used to derive the mass of the neutron – the second component of atomic nuclei besides the proton. After having already precisely weighed the electron and the proton, the nucleus of the ordinary hydrogen atom, in recent years, researchers around Klaus Blaum and Sven Sturm from the MPI for Nuclear Physics have now also put the deuteron, the nucleus of heavy hydrogen consisting of a proton and a neutron, and the HD⁺ molecular ion on the "precision scale". Since deuterium is rare and is usually easily replaced by the much more common normal hydrogen, Christoph Düllmann's research group in Mainz produced a tailor-made deuterium sample that fits the used apparatus perfectly.

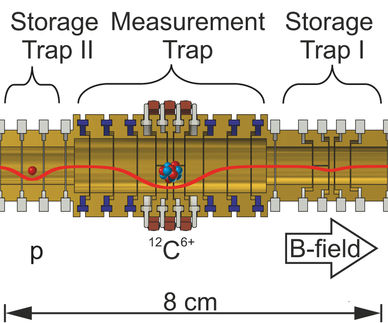

Penning traps have proven to be the best precision scales for ions. In such a trap, single charged particles can be trapped for a long time with the help of electric and magnetic fields. The trapped particle performs a characteristic motion in the trap, which is described by a frequency. This frequency depends on the mass of the trapped particle – heavier particles oscillate more slowly than lighter ones. If two different, individual ions are measured one after the other in the same trap, the ratio of the masses can be determined exactly – similar to a classical mechanical beam balance.

Sophisticated measurement technology for maximum precision

The mass standard for atoms is the carbon isotope ¹²C, which by definition weighs 12 atomic mass units. "Our Penning trap apparatus called LIONTRAP is located in a superconducting magnet in nearly perfect vacuum at a temperature of about 4 degrees above absolute zero (–269°C). We prepared a deuteron (D⁺) and a carbon ion (¹²C⁶⁺) in the apparatus, alternately transferred one of them from its storage trap to the precision trap located between the storage traps and measured its movement with highest precision," says Sascha Rau, who carried out the measurements in the context of his PhD, explaining the measuring principle. "The ratio of the frequencies of both ions obtained in this way directly gives the mass of the deuteron in atomic units." So, the carbon ion acts as a reference weight on the "beam balance".

When evaluating the measurement data, the physicists had to consider very carefully the influence of many unavoidable systematic effects. As a result, they obtained the mass of the deuteron as 2.013553212535(17) atomic units, with the number in parentheses indicating the uncertainty of the last digits. The mass of the hydrogen molecular ion HD⁺, determined by the same method, is 3.021378241561(61) atomic units.

The new value for the mass of the deuteron is the most accurate ever measured, but is significantly smaller than the tabulated reference value. "To validate our result, we calculated the mass of HD⁺ with this value and with the masses of the proton and the electron previously measured by us, as well as the known binding energy. The result is in excellent agreement with our directly measured value. In addition, the mass ratio of deuteron to proton derived from our data fits very well with the value directly measured by another group," says Sven Sturm with satisfaction. This consistency of the data underpins the used measurement methodology and suggests that the reference values should be corrected. In addition, the new data considerably reduces the discrepancies that previously existed among the masses of light nuclei. However, in order to fully resolve these discrepancies, further high-precision mass measurements – directly in atomic units – of super-heavy hydrogen (tritium) and of light helium are required.