A novel microscope operates on the quantum state of single electrons

We, and everything around us consists of molecules. The molecules are so tiny that even a speck of dust contains countless of them. The more fascinating it is that nowadays it is routinely possible to precisely image such molecules with a microscope called atomic force microscope. It works quite different form an optical microscope: it is based on sensing tiny forces between a tip and the molecule under study. Thereby, one can even image the internal structure of a molecule. Although one can watch the molecule this way, this does not imply knowing all its different properties. For instance, it is already very hard to determine, which kind of atoms the molecule consists of.

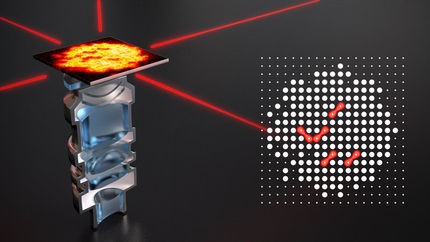

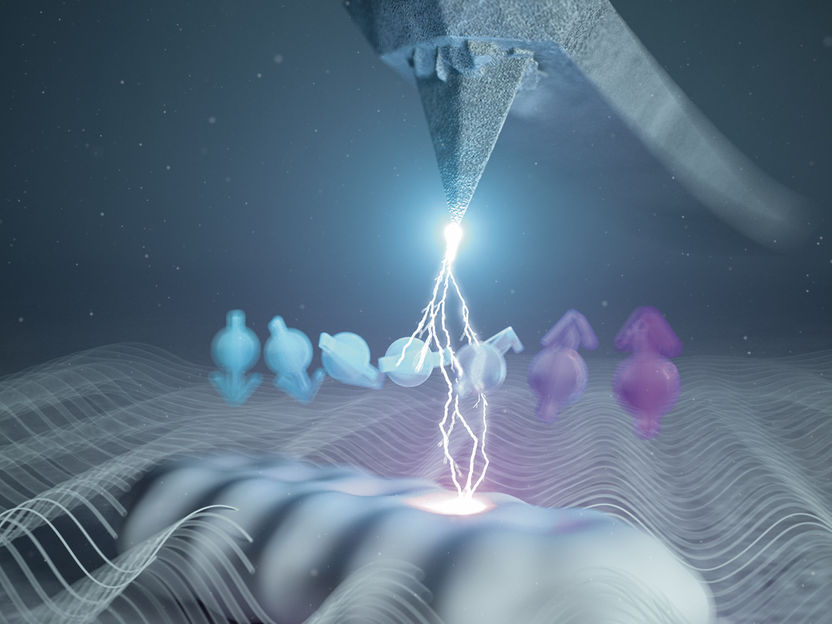

Artistic illustration of the integration of electron spin resonance in atomic force microscopy. The white structure at the bottom represents a single molecule, the arrows its spin quantum state and the wavy lines the radio-frequency magnetic field needed for the electron spin resonance, which is detected by the tip of the atomic force microscope.

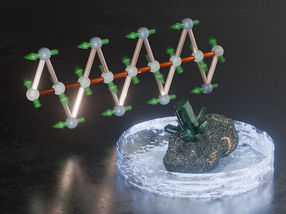

© Eugenio Vázquez

Luckily, there are other tools around that can determine the composition of molecules. One of them is electron spin resonance, which is based on similar principles as an MRI scanner in medicine. In electron spin resonance one usually needs, however, countless of molecules to obtain a signal that is large enough to be detectable. This way, one cannot access the properties of every molecule, but only their average.

Researchers at the University of Regensburg, led by Prof Dr Jascha Repp from the Institute of Experimental and Applied Physics at the UR, have now integrated electron spin resonance into atomic force microscopy. Importantly, the electron spin resonance is detected directly with the microscope’s tip, such that the signal comes from one individual molecule only. This way, they can characterize single molecules in a one-by-one fashion. This allowed to straightforwardly determine, of which atoms the molecule they just imaged is composed. “We could even discriminate molecules that do not differ in the type of atoms, that they were composed of, but only in their isotopes, namely, in the composition of the atoms' nuclei”, adds Lisanne Sellies, the first author of this study.

“Yet, we are even more intrigued by another possibility that electron spin resonance entails:” explains Prof. Dr. Repp, “this technique can be used to operate the spin-quantum state of the electrons present in the molecule.” In the illustration, this is depicted as the little colored arrows. But why is this interesting? Quantum computers store and process information that is encoded in a quantum state. To perform a calculation, quantum computers require to manipulate a quantum state without losing the information by so-called decoherence.

The researchers in Regensburg showed that with their new technique they could operate the quantum state of the spin in a single molecule many times before the state decohered. Since the microscopy technique allows to image the individual neighborhood of the molecule, the newly developed technique could help to understand how decoherence in a quantum computer depends on the atomic-scale environment, and – eventually – how to avoid it.

Original publication

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.