Detecting material defects in ship propellers

They can weigh up to 150 tons, and it's not uncommon for them to measure nine meters or more in diameter: the ship propellers on huge tankers, container ships and cruise liners are invisible giants. Damage to these massive propellers could render a ship unmaneuverable – with unpredictable consequences for people and the environment. Many defects do not come from external influences, but instead originate in the production or repair process. For example, when the molded parts are being cast, any turbulence could lead to sand inclusions and pores. Left undetected, critical imperfections could lead to breakage of a blade.

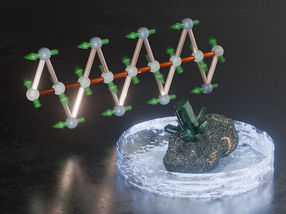

Until now, propellers have been inspected manually for inner defects when necessary. To make them visible, the inspector guides an ultrasound test probe over the component by hand – an error-prone procedure that fails to capture the entire volume of the component. This method cannot detect cracks inside the propeller in certain circumstances. To identify defects in a timely manner, researchers at the Fraunhofer Institute for Industrial Mathematics ITWM developed a mechanized ultrasound process that can be used for the non-destructive testing of complex components. The scientists received support from the GL Group (Germanischer Lloyd) and propeller manufacturer Wärtsilä Propulsion Netherlands.

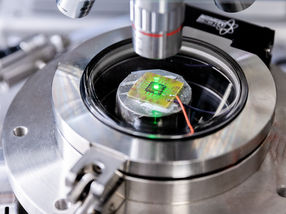

Mobile scanner can be positioned freely

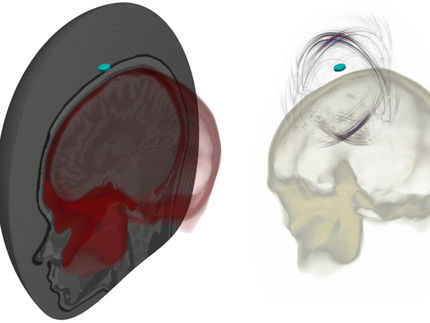

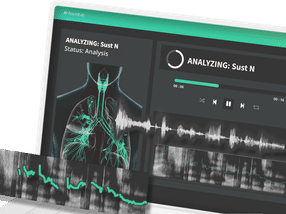

"With our mobile ultrasound test system, we can inspect copper-nickel-aluminum bronzes up to 450 millimeters thick and detect fissures down to a few millimeters in length. Because we emit the ultrasound at defined angles, we also find defects positioned at an angle to the surface", says Dr. Martin Spies of ITWM in Kaiserslautern. The system is capable of recording large volumes of digitized ultrasound test data, taking into account the many and variously intense curvatures of the propeller surface. The device currently scans test grids of 700 by 400 millimeters, achieving a rate of up to 100 millimeters per second. The mobile scanner can be positioned anywhere on the propeller, and, thanks to its suction feet, it can be attached in a horizontal as well as vertical test position. "We obtained the 3D data about the inside of the component by an imaging procedure known as SAFT. It provides a detailed display of inclusions and welding-seam defects. It basically works like computer tomography in medicine," explains Spies.

With the aid of special computational processes and algorithms, the experts have succeeded in reducing interference signals and intensifying error signals – a complicated task, since the various areas of the blade do not have a homogenously coarse grain. This can weaken the echo substantially. The specialists also use simulations to calculate in advance which ultrasound test probe they have to deploy.

The researchers use the mobile scan system for their on-site testing at foundries, at propeller manufacturers, on deck and in dry dock, and are currently improving scan times and 3D defect imaging. Only recently, they were able to put the efficiency of their procedure to the test at the world's largest shipbuilder in Korea. "The customer wanted to document the quality of its propellers, to gain an edge over the competition," says Spies. "With our procedure, we can test not only propellers but also other complex components made of materials that are difficult to test, like offshore components made of duplex steels," he stressed. ITWM researchers Alexander Dillhöfer, Hans Rieder and Dr. Martin Spies recently received the Innovation Award from the Deutsches Kupferinstitut for their outstanding accomplishments with copper and its alloys.

Most read news

Other news from the department research and development

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.