Rice University researchers optimize photoluminescent probes to study DNA and more

Sorting good data from bad is critical when analyzing microscopic structures like cells and their contents, according to researchers at Rice University. The trick is to find the right window of time through which to look.

A new paper by the Rice lab of Angel Martí, an assistant professor of chemistry and bioengineering, offers a methodology to optimize the sensitivity of photoluminescent probes using time-resolved spectroscopy. Martí and co-author Kewei Huang, a graduate student in his group, found their technique gave results nearly twice as good as standard fluorescence spectroscopy does when they probed for specific DNA sequences. Their results were reported in Analytical Chemistry.

In spectroscopy, chemicals and materials from proteins to nanotubes can be identified and tracked by their fluorescence - the light they return when excited by an input of energy, usually from a laser. In the kind of targeted spectroscopy practiced by Martí and his colleagues, a luminescent probe called a molecular beacon is designed to attach to a target like a DNA sequence and then light up.

Improving a probe's ability to detect ever smaller and harder-to-find targets is important to biologists, engineers and chemists who commonly work on the molecular scale to analyze cell structures, track disease or design tiny machines.

One problem, Martí said, has been that even in an experiment lasting a fraction of a second, a spectrometer can return too much information and obscure the data researchers actually want. "In standard fluorescence spectroscopy, you see noise that overlaps with the signal from your probe, the scattering from your solution or cuvettes, plus the noise from the detector," he said. The saving grace, he said, is that not all those signals last the same amount of time.

Time-resolved spectroscopy provides part of the answer, Martí said. Compared with standard spectroscopy, it's like taking a film instead of a snapshot. "We create a kind of movie that allows us to see a specific moment in the process where photoluminescence is occurring. Then we can filter out the shadows that obscure the measurement or spectra we're looking for," he said.

With samples loaded into the spectrometer, researchers yell "Action!" by firing a laser that excites the target. In an edit of the resulting "movie" (which can be done in real time by the spectrometer), they chop off the front and back to narrow the data set to a range that might last only 80-billionths of a second, when the probe signal is strongest and the background signals are absent.

But it's critical to know just the right window of time to look at, Martí said. That's where the Rice methodology removes any uncertainty. They let researchers analyze all the factors, such as the emission intensity and decay of the specific probe with and without the target and the anticipated level of background noise. The experiment can then maximize the signal-to-background noise ratio. The technique works even with probes that are less than optimal, he said.

In combination with a technique called fluorescence lifetime microscopy, the Rice calculations may improve results from other diagnostic tools that gather data over time, such as magnetic resonance imaging machines used by hospitals.

Martí said the equations were the common-sense results of years of working with fluorescent spectroscopy. But, he said, when he looked for materials to help teach his students how to use time-resolved techniques to improve probes' resolution, he found none.

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

See the theme worlds for related content

Topic world Fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescence microscopy has revolutionized life sciences, biotechnology and pharmaceuticals. With its ability to visualize specific molecules and structures in cells and tissues through fluorescent markers, it offers unique insights at the molecular and cellular level. With its high sensitivity and resolution, fluorescence microscopy facilitates the understanding of complex biological processes and drives innovation in therapy and diagnostics.

Topic world Fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescence microscopy has revolutionized life sciences, biotechnology and pharmaceuticals. With its ability to visualize specific molecules and structures in cells and tissues through fluorescent markers, it offers unique insights at the molecular and cellular level. With its high sensitivity and resolution, fluorescence microscopy facilitates the understanding of complex biological processes and drives innovation in therapy and diagnostics.

Topic World Spectroscopy

Investigation with spectroscopy gives us unique insights into the composition and structure of materials. From UV-Vis spectroscopy to infrared and Raman spectroscopy to fluorescence and atomic absorption spectroscopy, spectroscopy offers us a wide range of analytical techniques to precisely characterize substances. Immerse yourself in the fascinating world of spectroscopy!

Topic World Spectroscopy

Investigation with spectroscopy gives us unique insights into the composition and structure of materials. From UV-Vis spectroscopy to infrared and Raman spectroscopy to fluorescence and atomic absorption spectroscopy, spectroscopy offers us a wide range of analytical techniques to precisely characterize substances. Immerse yourself in the fascinating world of spectroscopy!

Last viewed contents

REACH: Late Pre-Registration ends in November 2009 for some chemicals and companies

Mobile DNA elements in woolly mammoth genome give new clues to mammalian evolution

DPZ-Researchers develop suitcase laboratory for rapid detection of the Ebola virus - New method is 6 to 10 times faster than the current techniques with equal sensitivity

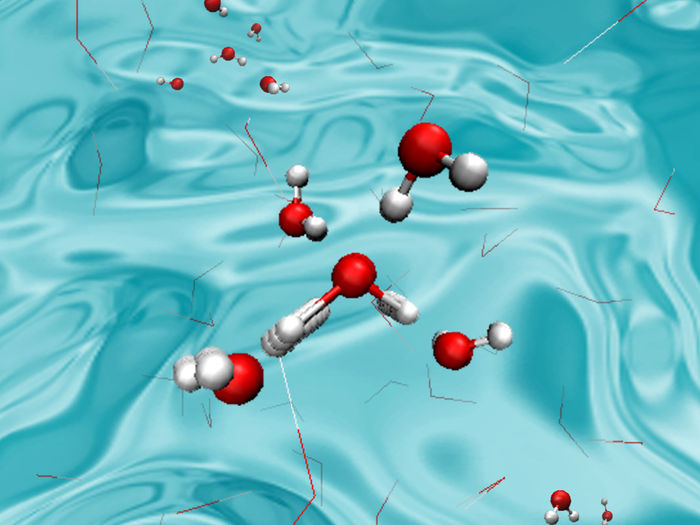

Researchers develop procedure to interpret x-ray emission spectra of liquid water - Study helping to advance the understanding of the structure of water