UF researchers to test method for predicting complications in trauma patients

University of Florida researchers have received a four-year, $1.8 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to verify the effectiveness of a new genomic screening method that could help predict possible infections and complications in patients with severe traumatic injuries.

These complications, which often appear in the lungs and kidneys can develop suddenly and are notoriously difficult and costly to treat, causing death or preventing full recovery for hundreds of thousands of trauma patients in the United States each year. UF researchers helped develop the new technique.

“In a world of limited resources, the new test is going to help identify those patients, within hours of their injury, who are likely to have problems and require more aggressive management,” said Lyle Moldawer, Ph.D., a UF professor of surgery and the department’s vice chair for research. “We’re going to know before their symptoms appear whether they’re at risk of getting complications. What we know with trauma and infection is, the earlier you intervene, the better the results are.”

The researchers predict the test will allow clinicians to more effectively allocate health resources to patients at the greatest risk of infection and organ problems, and will help them save tens of thousands of lives each year. It also might help reduce health care costs by several billion dollars annually, UF researchers estimate.

Researchers from UF Health and other institutions collaborated to develop the technique based on research done and data collected through a research program that lasted until 2010 and was funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

The process involves screening small samples of a patient’s blood for the abnormal expression of 63 specific genes. Each gene in the body carries chemical instructions that direct cells to build proteins and perform essential functions. Normal gene expression occurs when chains of nucleic acids, chemically transmit these instructions to a cell, which then completes the assigned task. Abnormal expression occurs when a cell produces too much or too little of the specified protein.

By collecting and analyzing 10 years’ worth of patient data, the researchers identified 63 specific genes associated with increased risk of complications. These genes are expressed abnormally in trauma patients whose recoveries are plagued by organ problems and related difficulties. They also created a testing metric to allow clinicians to evaluate a patient’s genomic expression based on a single score, rather than 63 individual ones. A May article in the journal Critical Care Medicine describes the group’s creation of the metric and their previous verification of the testing method in about 150 trauma patients. The NIH grant will fund efforts to verify it in about 250 additional patients.

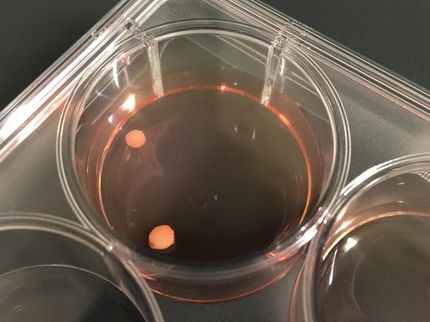

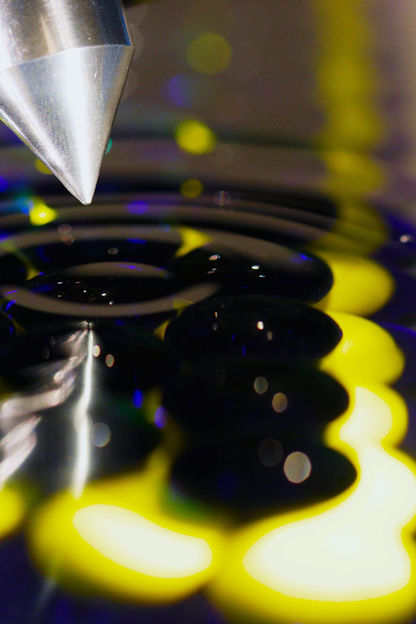

The test requires isolating white blood cells from a blood sample taken within the first 24 hours after trauma, then inspecting how the genes in question are expressed within them. To remove the white blood cells from the sample, the researchers use a miniature cassette, called a microfluidics cassette, developed several years ago by investigators from Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital. UF Health scientists helped test the cassette during its development.

The test produces results in less than 12 hours. Before the cassette, the process of analyzing body fluid samples for gene or protein expression took as long as a week. The new technique’s quick turnaround time provides timely treatment for patients whose results indicate they will suffer serious complications during recovery. Interventions that may help these patients include existing drugs, as well as some in development or testing, and a special diet.

Such drugs will not help patients whose injuries are too extreme to survive, or those who are not genomically inclined to experience complications in their recoveries, said Moldawer, the senior author of the journal article. By using the new testing method to find patients who will benefit from the drugs, health care providers can administer the drugs early to the right people. Because these drugs can cause significant side effects, patients don’t typically receive them until they exhibit signs of persistent organ problems and are very ill.

Researchers say weeding out patients who should not receive the medications because they are not prone to such organ problems would allow trials of the drugs to be conducted with much smaller groups than are currently used.

“What we would expect is that if this is validated, then we can reduce the size and the cost of clinical trials in patients with trauma and sepsis by 60 to 70 percent,” Moldawer said. “So, a $100 million clinical trial with 2,000 patients could be done with 800 patients for less than half the cost and time.”

If viable, the new test would bring a solution to trauma patients and health care providers that researchers have sought unsuccessfully for decades.

“This is going to personalize medicine,” Moldawer said. “Every patient with trauma is going to be admitted and they’re going to get this test done. With some of them, providers are going to say ‘That patient looks OK. But well, look at the score he’s got. That tells me something’s likely going to happen. We better aggressively get him off the ventilator, look closely for evidence of persistent organ problems, consider additional therapies.’ Because we didn’t wait until persistent organ problems appeared and the patient crashed, the probable results for that patient are better outcomes and less hospital expense.”