Diverging thermal conductivity

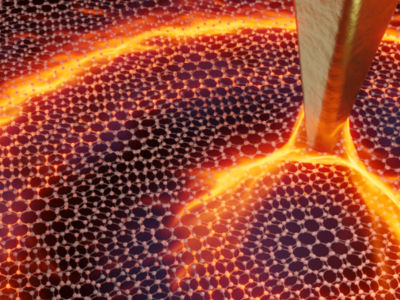

Physicists at the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research show unlimited heat conduction in graphene.

Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research (MPI-P) in Mainz and the National University of Singapore have attested that the thermal conductivity of graphene diverges with the size of the samples. This discovery challenges the fundamental laws of heat conduction for extended materials.

Davide Donadio, head of a Max Planck Research Group at the MPI-P, and his partner from Singapore were able to predict this phenomenon with computer simulations and to verify it in experiments. Their research and their results have now been presented in "Nature Communications".

"We recognized mechanisms of heat transfer that actually contradict Fourier’s law in the micrometer scale. Now all the previous experimental measurements of the thermal conductivity of graphene need to be reinterpreted. The very concept of thermal conductivity as an intrinsic property does not hold for graphene, at least for patches as large as several micrometers", says Davide Donadio.

Are material constants alterable after all?

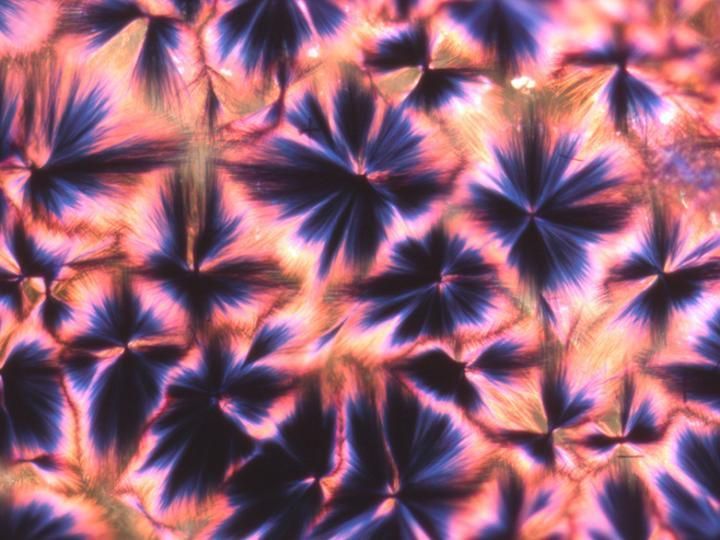

The French physicist Joseph Fourier had postulated the laws of heat propagation in solids. Accordingly, thermal conductivity is an intrinsic material property that is normally independent of size or shape. In graphene, a two-dimensional layer of carbon atoms, it is not the case, as our scientists now found out. With experiments and computer simulations, they found that the thermal conductivity logarithmically increases as a function of the size of the graphene samples: i.e., the longer the graphene patches, the more heat can be transferred per length unit. This is another unique property of this highly praised wonder material that is graphene: it is chemically very stable, flexible, a hundred times more tear-resistant than steel and at the same time very light. Graphene was already known to be an excellent heat conductor: The novelty here is that its thermal conductivity, which was so far regarded as a material constant, varies as the length of graphene increases. After analyzing the simulations, Davide Donadio found that this feature stems from the combination of reduced dimensionality and stiff chemical bonding, which make thermal vibration propagate with minimal dissipation at non-equilibrium conditions.

Optimum cooling for nanoelectronics

In the micro- and nano-electronics, heat is the limiting factor for smaller and more efficient components. Therefore, materials with virtually unlimited thermal conductivity hold an enormous potential for this kind of applications. Materials with outstanding electronic properties that are self-cooling too, as graphene might be, are the dream of every electronics engineer.

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.