Scientists create novel imaging technique with potential for medical diagnostics

A unique new imaging method, called "polarized nuclear imaging" - combining powerful aspects of both magnetic resonance imaging and gamma-ray imaging and developed by two physicists in the University of Virginia's departments of Physics and Radiology has potential for new types of high-resolution medical diagnostics as well as industrial and physics research applications.

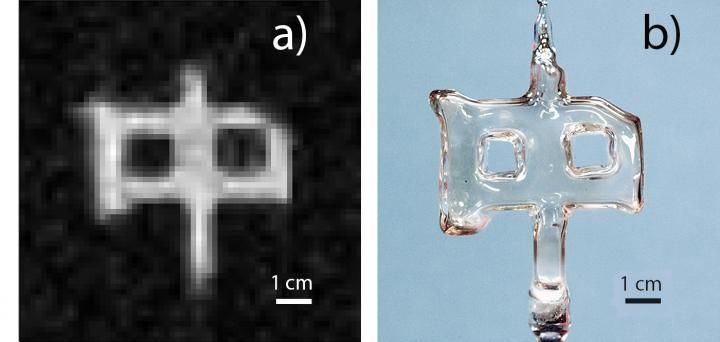

Photo A is an image of a sealed glass cell obtained by UVA physicists by combining magnetic-resonance techniques with the detection of gamma rays emitted by an isotope of xenon contained within the cell. Image B is an ordinary photograph of the glass cell.

University of Virginia

"This method makes possible a truly new, absolutely different class of medical diagnostics," said Wilson Miller, who, along with his colleague Gordon Cates, directed the research. "We're combining the advantages of using highly detectable nuclear tracers with the spectral sensitivity and diagnostic power of MRI techniques."

A paper detailing the new imaging modality and related spectroscopic techniques, for which a patent is pending, appeared recently in the journal Nature.

"We have demonstrated the feasibility of the new technique by producing a proof-of-principle image in a manner never before accomplished," Cates said. "In our technique, rather than imaging protons in water, as in MRI, we image a radioactive isotope of xenon that has been polarized using laser techniques."

Cates and his colleagues believe that the technique, once refined, could provide a new, relatively inexpensive way to visualize the gas space of the lungs by having patients inhale a gas containing the isotopes and using PNI to produce an image. The method likewise might work to image targeted areas of the body by injecting isotopes into the bloodstream. Because the technique would use such small quantities of tracer material, when it comes to medical use, the radioactivity would pose little to no danger to people.

Since magnetic resonance imaging has never before been used in combination with radioactive tracers, there is a potential for obtaining new types of diagnostic information that have not been available previously.

MRI, which is widely used for detecting cancer and other abnormalities in the body, is effective because it uses a variety of contrast mechanisms to sort out specific characteristics in an image. And highly sensitive gamma-ray detectors can resolve miniscule amounts of radioactive tracer material, key to homing in on points of particular interest. The new UVA technique uses magnetic resonance to obtain the spatial information, and then collects image information by detecting gamma rays produced by the tracer material - an isotope of xenon Xe-131m, which is a byproduct of Iodine 131 (used for treatment of thyroid problems).

"Unlike MRI, which detects faint radio waves, we detect gamma rays that are emitted from the xenon isotope," Cates said. "Since it is possible to detect a gamma ray from even a single atom, we gain an enormous increase in imaging sensitivity, and dramatically reduce the amount of material needed for performing magnetic-resonance techniques."

As an example, had Cates and Miller filled their imaging subject - in this case a small glass cell shaped like the Chinese symbol for the word "middle" - with water rather than the radioactive isotope, they would have needed about 10 billion times more water molecules than the number of isotope atoms they used to achieve the same image quality. This means that with minute quantities of material, they can achieve detailed imagery using magnetic-resonance techniques that would otherwise be impossible using a radioactive tracer.

The publication includes the first-ever published image using polarized nuclear imaging. The researchers say the quality of that picture far exceeds the first image ever produced using MRI, which was first published in 1973.

"There was once a first X-ray image, and a first CT-scan image, and first MRI image," Miller said. "We have now produced the first image of a new technology, PNI, which someday may be as much in use as those others."

The authors note that considerable work still needs to be done to demonstrate the utility of the new technique in living subjects, but the unique approach "represents an exciting new technology."

To develop it for practical use, the researchers say they would need to increase the size of the detectors or the amounts of tracer material, and they are seeking alternative radioactive isotopes that would retain their polarization once inside a living subject. There are enough possibilities, however, that they are optimistic, and anticipate the possibility of many applications.

In biological systems, gas imaging already appears to be practical, as do applications involving non-biological systems, such as nuclear physics research.