Surprising twist in confined liquid crystals

A simple route to developing new sensors

Researchers at Georgia Institute of Technology have found a material used for decades to color food items ranging from corn chips to ice creams could potentially have uses far beyond food dyes.

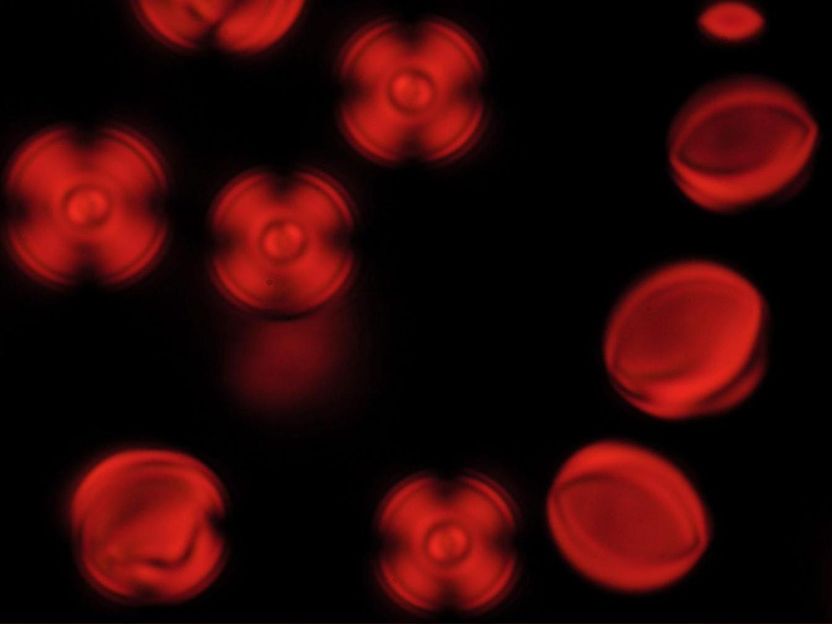

This is a magnified image of liquid crystals confined to spherical tactoids.

Georgia Tech

In a study the researchers described how a class of water soluble liquid crystals, called lyotropic chromonic liquid crystals, exhibited unexpected characteristics that could be harnessed for use in sensors and other potential applications.

"We were seeking to understand the aggregation and phase behavior of these plank-like molecules as a function of temperature and concentration," said Karthik Nayani, a former Georgia Tech student who worked on the problem. "When observed under crossed polarizers in an optical microscope, liquid crystals can exhibit beautiful textures that hint toward how the molecules themselves are arranged."

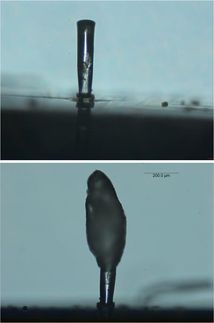

To answer some fundamental questions pertaining to the material's phase behavior, the researchers used the microscopes to observe the molecules' textures when they were confined to droplets known as tactoids.

"Surprisingly, we found a configuration that hasn't been seen before in the 70 years that people have been studying liquid crystals," said Mohan Srinivasarao, a professor in the Georgia Tech School of Materials Science and Engineering. "Historically, liquid crystals in tactoids conform to what is known as a bipolar and a bipolar configuration with a twist. At lower concentrations, we found that these liquid crystals arrange in a concentric fashion, but one that appears to be free of a singular defect."

The researchers then used a simple model of the aggregation behavior of these molecules to explain these surprising results. Further, spectroscopic experiments using polarized Raman microscopy were performed to confirm their findings.

These new findings add to the growing understanding of how chromonic liquid crystals could be used in sensing applications, Srinivasarao said. The crystals are water soluble and respond dramatically to being confined to certain patterns -- such as tactoidal droplets -- concentrations, and temperatures. The material's responsiveness to altering its environment could potentially be used to sense the chirality -- or "handedness" -- of molecules, Srinivasarao said.

"These materials don't have a chiral center but they exhibit a chiral structure," Srinivasarao said. "That in itself is very interesting."

That finding could be useful in answering those kinds of questions, he said.

"There are lots of people studying why on planet Earth all amino acids have a handedness, one and not the other," Srinivasarao said. "Where does this handedness come from?"

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.