NMR technique offers 'molecular window' into living organisms

A novel technique developed by University of Toronto Scarborough researchers can for the first time get a high-resolution profile of which molecules are present inside a living organism.

A novel NMR technique developed at U of T Scarborough has the potential for noninvasive disease diagnosis using current MRI technology.

University of Toronto Scarborough

"In a way we've developed this molecular window that can look inside a living system and extract a full metabolic profile," says Professor Andre Simpson, who led research into developing the new technique that uses nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) technology.

"Getting a sense of which molecules are in a tissue sample is important if you want to know if it's cancerous, or if you want to know if certain environmental contaminants are harming cells inside the body."

Until now traditional NMR techniques haven't been able provide high-resolution profiles of living organisms because of magnetic distortions from the sample itself. The analogy Simpson gives is that it's like being in a helicopter over a stadium while trying to talk to people at a concert down below. It's incredibly difficult to communicate because of the noise distortion, but if you give both a walkie-talkie, it makes communication much easier.

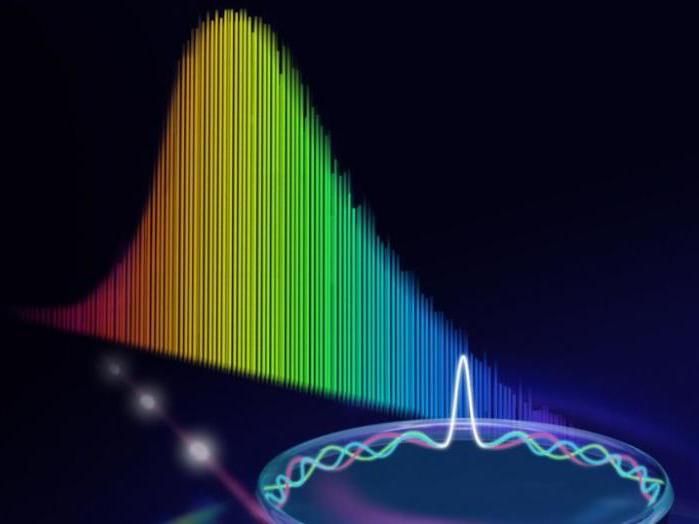

Simpson and his team were able to overcome the magnetic distortion problem by creating tiny communication channels based on something called long-range dipole interactions between molecules. In other words, whereas before only a snapshot of an object can be given this new technique can offer a complete chemical make-up of molecules within the object.

NMR technology is able to generate a powerful magnetic field, so powerful that atomic nuclei can be made to absorb and reemit the energy in distinct patterns, revealing a unique molecular signature. Simpson's work focuses on environmental NMR but he says there's great medical potential for this new technique since it can also be used in medical imaging techniques like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

"It could have implications for disease diagnosis and a deeper understanding of how important biological processes work," says Simpson, adding the technique is easily programmable and can be translated to work on existing modern MRI systems found in hospitals.

He points to specific molecules called cancer biomarkers that are unique to diseased tissue. The new approach holds potential to detect these signatures without resorting to surgery and determine whether a growth is cancerous or benign directly from the MRI alone.

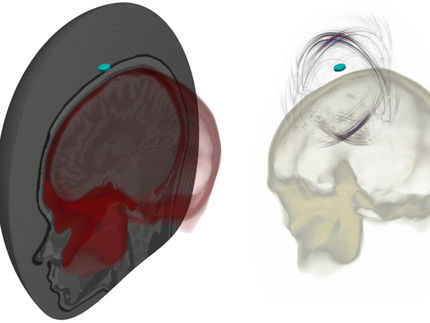

It also has the potential to tell us how the brain works. Current MRI methods can tell which part of the brain "lights up" in response to stimuli like fear or happiness, but those just indicate which part of the brain is responsible. The new technique can potentially be used to look inside those locations and reveal the chemicals actually causing the response.

"It could mark an important step in unraveling the biochemistry of the brain," says Simpson.

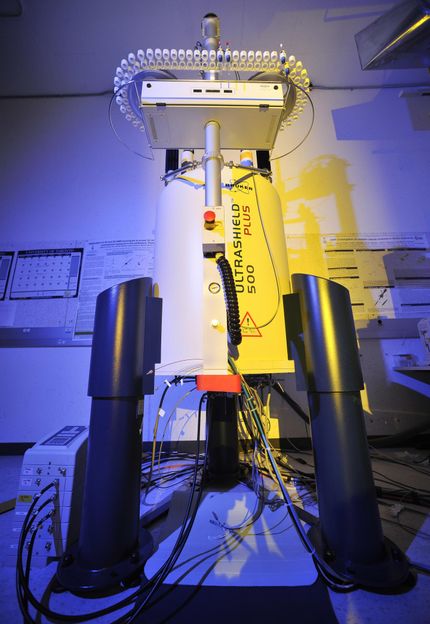

Simpson has been working on perfecting the technique for more than three years with colleagues at Bruker BioSpin, a scientific instruments company that specializes in developing NMR technology. The technique is based on some unexpected scientific concepts that were discovered in 1995, which at the time were described as impossible and crazed by many researchers.

The technique developed by Simpson and his team, including PhD student Ioana Fugariu, builds upon these early discoveries and is published in the journal Angewandte Chemie. The work was supported by Mark Krembil of the Krembil Foundation and the Natural Sciences Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

Simpson says the next step for the research is to test it on human samples. He adds that since the technique detects all metabolites equally there's also potential for non-targeted discovery, that is, finding pathologies or processes you weren't even looking for in the first place.

"Since you can see metabolites in a sample that you weren't able to see before, you can now identify molecules that may indicate there's a problem," he says.

"You can then determine whether you need further testing or surgery. So the potential for this technique is truly exciting."