Immune cells may heal bleeding brain after strokes

While immune cells called neutrophils are known to act as infantry in the body's war on germs, a National Institutes of Health-funded study suggests they can act as medics as well. By studying rodents, researchers showed that instead of attacking germs, some neutrophils may help heal the brain after an intracerebral hemorrhage, a form of stroke caused by ruptured blood vessels. The study suggests that two neutrophil-related proteins may play critical roles in protecting the brain from stroke-induced damage and could be used as treatments for intracerebral hemorrhage.

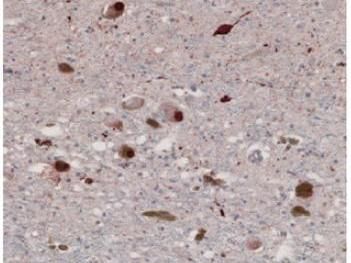

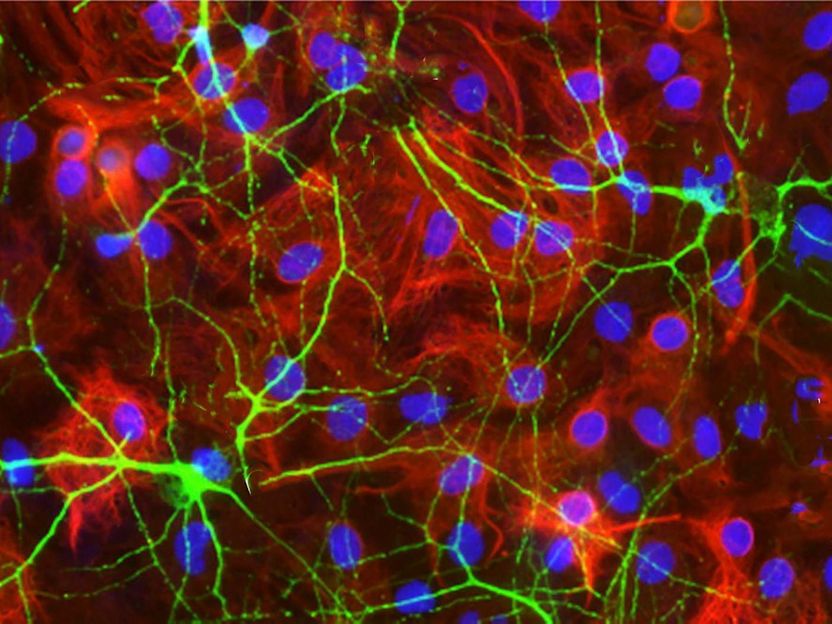

Researchers studied how immune cells called neutrophils may help protect the brain from damage caused by intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke.

Courtesy of Aronowski lab, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston.

"Intracerebral hemorrhage is a damaging and often fatal form of stroke for which there are no effective medicines," said Jaroslaw Aronowski, M.D., Ph.D., professor, department of neurology, at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, and senior author of the study "Our results are a hopeful first step towards developing a treatment for this devastating form of stroke."

Accounting for 10 to 15 percent of all strokes, intracerebral hemorrhages happen when blood vessels rupture and leak blood into the brain, often leading to death or long-term disability. Chronic high blood pressure is the leading risk factor for these types of strokes. The initial phase of damage appears to be caused by the pressure of blood leaking into the brain. Over time, further damage may be caused by the accumulation of toxic levels of blood products, infiltrating immune cells, and swelling.

Decades of research suggest that neutrophils are some of the earliest immune cells to respond to a hemorrhage, and that they may both harm and heal the brain. In this study, the researchers found that interleukin-27 (IL-27), a protein that controls the activity of immune cells, may shift the role of neutrophils from harming the brain to helping with recovery.

Injections of IL-27 after a hemorrhage helped mice recover. Days after the strokes, the treated mice had better mobility, including walking, limb stretching and navigating holes in a floor. In contrast, injections of an antibody that blocked natural IL-27 activity slowed recovery. The brains of the mice treated with IL-27 also showed less damage. They had less swelling around the hemorrhages and lower levels of iron and the blood protein hemoglobin, both of which are toxic at high levels.

"This study shines a spotlight on the critical role the immune system may play in helping the brain heal after a hemorrhage or stroke and opens new avenues for stroke treatment strategies," said Jim Koenig, Ph.D., program director at the NIH's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Neutrophils are born in bone marrow and carry chemicals in hundreds of densely filled packets called granules, which look like dark spots under a microscope. Typically, when the body senses bacteria or an injury, neutrophils rush to the invasion site and release germ killing chemicals from the granules. This appears to happen minutes after a hemorrhagic stroke.

In this study, the researchers suggested that after a hemorrhagic stroke the brain secretes high levels of IL-27, which leads to a second wave of neutrophils arriving with granules filled with higher amounts of healing molecules. IL-27 levels were elevated in the brain and blood of the mice an hour after hemorrhages and stayed high for three days, peaking at 24 hours later. Further experiments suggested that brain cells called microglia produced the IL-27 in response to the presence of red blood cells.

Once released, IL-27 molecules appeared to travel to the bones of the mice, infiltrated the marrow, and changed the role newborn neutrophils played in response to a stroke. When the researchers extracted newborn neutrophils from the bones of mice and treated them with IL-27, the chemical raised the activity of genes associated with healing, especially lactoferrin, while reducing the activity of genes associated with killing cells. Conversely, treating mice with an IL-27 neutralizing antibody after a hemorrhage lowered lactoferrin gene activity.

"Our results suggested that IL-27 links the brain to the bones," said Dr. Aronowski. "We can use these results as a source for ideas for developing potential treatments for hemorrhagic stroke."

Finally, the researchers showed the iron binding protein lactoferrin may protect the brain from intracerebral hemorrhagic strokes. Mice and rats injected with lactoferrin 30 minutes after hemorrhages recovered faster and had reduced brain damage as compared to animals given placebos. In one set of experiments, the researchers found that giving mice lactoferrin 24 hours after a stroke was also effective.

"Lactoferrin appears to have a long treatment window," said Dr. Aronowski. "This means lactoferrin might one day be used to help patients recover from intracerebral hemorrhage."

Dr. Aronowski's team is taking the next steps towards testing lactoferrin treatment in patients.