Genome architecture caught in motion

Researchers at The Wistar Institute have uncovered new aspects of the three-dimensional organization of the genome, specifically how the genetic material is compacted and de-compacted in a timely fashion during the different phases of the cell cycle.

"We are just starting to appreciate that the way our genome is spatially organized in our cells has a profound impact on its function," said lead author of the study Ken-ichi Noma, Ph.D., associate professor in the Gene Expression and Regulation Program at Wistar. "Deciphering the three-dimensional structure of chromatin is essential to understanding key functions like transcription, DNA replication and repair."

The genetic information contained inside each of our cells is encoded by several feet worth of DNA molecules. Such an enormous amount of genetic material is packed into a microscopic space by folding it into a highly organized complex of DNA and proteins called chromatin. Although already significantly compacted, chromatin needs to be further condensed upon entry into mitosis, the process that divides each cell into two identical cells, in order to faithfully segregate the genetic material. Just as we pack up household belongings into smaller boxes when we relocate into a new house, it is easier to move and divide the DNA in the form of compacted chromosomes. This process has been known for several decades, yet the underlying molecular mechanisms that govern chromatin condensation and de-condensation are still poorly defined.

The Noma lab has extensively studied the mechanisms of genome organization using fission yeast as a model organism because it shares some important features with human cells while having a much smaller genome.

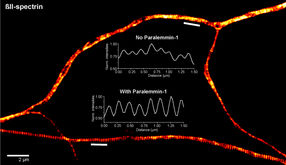

Noma and colleagues have previously described how two protein complexes called condensin and cohesin mediate the formation of functional genome-organizing structures called topological domains by establishing contacts that bring distantly located DNA regions closer together. Specifically, cohesin mediates local contacts, forming small topological chromatin domains, whereas condensin drives longer-range contacts, organizing larger domains.

In the new study, the lab applied similar genomic methodology to dissect the condensation and de-condensation of chromatin in topological domains over time, following the formation and decay of chromatin contacts throughout the different phases of the cell cycle. They discovered that the larger domains mediated by condensin are formed during mitosis, whereas the smaller, local domains mediated by cohesin remain stable throughout the whole cycle.

"Contrary to what was generally assumed in the field, we find that condensation and de-condensation of the chromatin domains happen very gradually and the cells oscillate smoothly between more and less condensed chromatin states," said first author of the study Hideki Tanizawa, Ph.D., an associate staff scientist in the Noma lab.

Alterations of the three-dimensional structures of the genome are linked to genetic diseases and cancer, presenting a powerful example of how basic cellular processes are relevant for disease. "The field is still in an early discovery phase but our study adds new insight into a fundamental biological process that may assist the development of novel therapeutic strategies in the future," added Noma.

Original publication

Hideki Tanizawa, Kyoung-Dong Kim, Osamu Iwasaki & Ken-ichi Noma; "Architectural alterations of the fission yeast genome during the cell cycle"; Nature Structural & Molecular Biology; 2017

Original publication

Hideki Tanizawa, Kyoung-Dong Kim, Osamu Iwasaki & Ken-ichi Noma; "Architectural alterations of the fission yeast genome during the cell cycle"; Nature Structural & Molecular Biology; 2017

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.