First nanoscale image of soil reveals an 'incredible' variety, rich with patterns

A handful of soil is a lot like a banana, strawberry and apple smoothie: Blended all together, it is hard to tell what's in there, especially if you have never tasted the fruits before. But when you look at soil's organic carbon closely, it has an incredible variety of known compounds. And looking closely is exactly what Cornell researchers have done for the first time - at a scale of 50 nanometers. Until now, handfuls of soil humus (or the organic component of soil, formed by the Decomposition of leaves and other plant material by soil microorganisms) looked remarkably similar.

According to a study published in Nature Geoscience, knowing the structure and detailed composition of soil carbon could provide a better understanding of the chemical processes that cycle organic matter in soil. For example, the research may help scientists understand what happens when materials in the soil get wet, warm or cool and how soils sequester carbon, which has implications for climate change.

"There is this incredible nanoscale heterogeneity of organic matter in terms of soil," said Johannes Lehmann, a Cornell associate professor of crop and soil sciences and lead author of the study. "None of these compounds that you can see on a nanoscale level looks anything close to the sum of the entire organic matter."

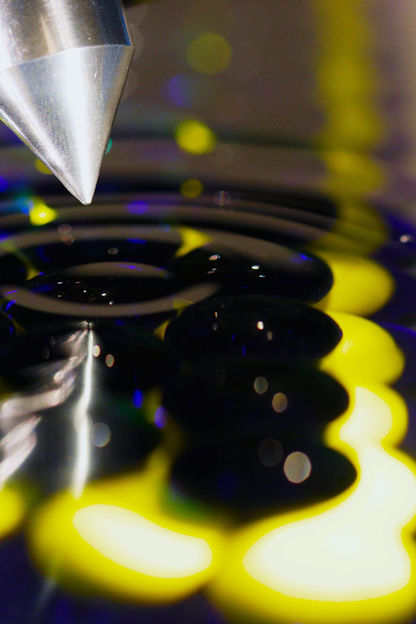

The soil measurements (actually, images produced by a highly focused X-ray beam) were made at the National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Laboratory using an X-ray spectromicroscopy method developed by physicists at the State University of New York, Stony Brook. The method allowed the researchers to identify forms of organic carbon in the samples.

While the composition of organic carbon in soils from North America, Panama, Brazil, Kenya or New Zealand proved remarkably similar within each sample, the researchers found that within spaces separated by mere micrometers, soils from any of these locations showed striking variation in their compositions. For example, the compounds that "hang on the right and left of a clay mineral may be completely different," said Lehmann.

The researchers were also able to identify the origins of some of the nano-sized compounds, determining that some of them, for example, were microbe excretions and decomposed leaves. The researchers also recognized patterns of where types of compounds are likely to be found at the nanoscale.

"Now we can start locating certain compounds," Lehmann said. "We find black carbon as distinct particles in pores, whereas we find microbial products smeared around surfaces of minerals."

The method now allows researchers to break soil down, separate compounds, conduct experiments on individual compounds and better understand the interactions, Lehmann said.

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.