Models present new view of nanoscale friction

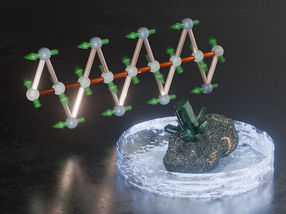

To understand friction on a very small scale, a team of University of Wisconsin-Madison engineers had to think big. Friction is a force that affects any application where moving parts come into contact; the more surface contact there is, the stronger the force. At the nanoscale friction can wreak havoc on tiny devices made from only a small number of atoms or molecules. With their high surface-to-volume ratio, nanomaterials are especially susceptible to the forces of friction.

But researchers have trouble describing friction at such small scales because existing theories are not consistent with how nanomaterials actually behave. Through computer simulations, the group demonstrated that friction at the atomic level behaves similarly to friction generated between large objects. Five hundred years after Leonardo da Vinci discovered the basic friction laws for large objects, the UW-Madison team has shown that similar laws apply at the nanoscale.

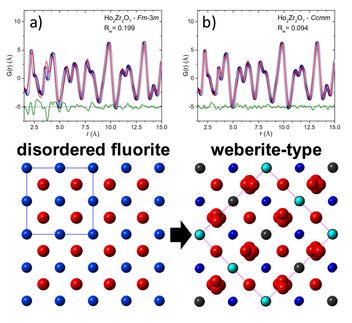

The team, which was led by Izabela Szlufarska, an assistant professor of materials science and engineering, and included materials science and engineering graduate student Yifei Mo and mechanical engineering assistant professor Kevin Turner, published its findings in Nature. Current nanoscale friction theories are based on the idea that nanoscale surfaces are smooth, but, in reality, the surfaces resemble a mountain range, where each peak corresponds to an atom or a molecule.

The UW-Madison team performed computer simulations that looked at nanoscale materials as a collection of atoms, monitoring their positions and interactions throughout the entire sliding process. "For the first time, we modeled friction at length scales very similar to experiments, while maintaining atomic resolution and realistic interactions between atoms," say Szlufarska.

The team discovered simple laws of nanoscale friction. They found that friction is proportional to the number of atoms that interact between two nanoscale surfaces. The researchers' simulations showed that, at the nanoscale, materials in contact behave more like large rough objects rubbing against each other, rather than as two perfectly smooth surfaces, as was previously imagined. "When you look at it closely, the surface is made of atoms, so the contact is actually rough," says Szlufarska.

The team's simulation data correlates very well with recorded experimental data — something that previous models have failed to accomplish. Szlufarska hopes to use the simulations as a tool to understand what mechanisms contribute to friction on both the nano- and macroscale.

"Nobody is able to predict friction or design materials with desired friction properties — we measure a lot of friction coefficients for different materials, but it's not really clear how to relate them to the properties of the material," she explains. "The origin of friction is really an open and growing research field."

Most read news

Organizations

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.