Scientists decode genome of deadly parasitic worm

Scientists have sequenced the genome of the parasite that causes intestinal schistosomiasis (also known as bilharzia or snail fever), a devastating tropical disease that afflicts more than 200 million people in the developing world.

Najib El-Sayed, associate professor in the University of Maryland's College of Chemical and Life Sciences, led the transatlantic research team, along with Matthew Berriman of the UK's Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. Their work is published in the July 16, 2009 edition of Nature.

Schistosomiasis is one of several neglected tropical diseases prevalent across much of Africa, Asia, and South America and affects mainly poor populations living in areas where water is unsafe, sanitation inadequate, and basic health care unavailable. It impacts adults and children's capacity to work and learn, and often leads to death. Knowing this parasite's genome sequence, scientists will now be able to develop much-needed new treatments for schistosomiasis, for which a vaccine does not yet exist. The drug commonly used to treat this parasitic infection does not prevent re-infection, and there are growing reports of drug resistance and treatment failures.

"We have used state of the art genetic and computational approaches to decipher the genome of this pathogen and to facilitate drug discovery," said El-Sayed, senior author of the paper. "Many promising leads for drug development targets have emerged."

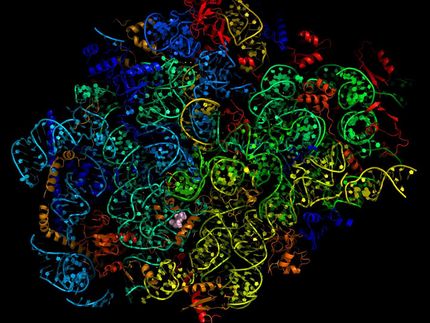

The paper reports the analysis of approximately 12,000 genes encoded in the nuclear DNA of Schistosoma mansoni, the flatworm that causes schistosomiasis. This comprehensive genome sequence enabled researchers to map out metabolic networks that are essential to survival of the parasite, thereby revealing potential areas of vulnerability. Through bioinformatics and chemogenomic screens, the study also explores cost effective ways to develop new therapies, such as the possibility that existing pharmaceutical drugs might be used to target schistosomiasis.

"We deliberately looked for similarities between us and the parasite so that we may be able to exploit the activities of existing drugs, marketed for different purposes" said Berriman (joint senior author) of the study.

The researchers compared S. mansoni genes with known 'druggable' protein targets of the human host and human-infective pathogens in use by pharmaceuticals on the market; matches indicate potential for existing drugs to be repurposed as anti-schistosomal drugs.

"The accomplishment of sequencing the S. mansoni genome is the critical first step in developing the drugs and vaccines we urgently need to effectively combat schistosomiasis," said Peter Hotez, Distinguished Research Professor and Chair of the Department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Tropical Medicine at George Washington University and President of the Sabin Vaccine Institute. "It is one of the most important neglected tropical diseases, with evidence suggesting that it may be as important as better known conditions such as malaria or HIV, because of the number of people it affects with chronic, debilitating infections."

For a sidebar with S. mansoni image: The S. mansoni parasite has a complex life cycle, perpetuated by poor water conditions. The parasite's eggs hatch in water, enter into snail hosts, then travel to human hosts through contaminated water sources, such as bathing and swimming areas. The mature fluke worm grows in the human blood vessel system, depositing eggs around the bladder or intestines, which triggers the formation of excess connective tissue in those regions. The parasite's eggs are passed to the liver or exit through the urine or feces, continuing the cycle of infection.

Most read news

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.