The limits of friction

friction is created when two surfaces slide one on top of the other. Since this consumes additional energy, this so-called sliding friction is considered an irksome yet inevitable aspect of dynamic processes. However, to set a stationary object in motion, its static friction must be overcome first. In collaboration with their Italian colleagues, researchers from the University of Konstanz have demonstrated how to entirely suppress static friction between two surfaces. This means that even a minuscule force suffices to set objects in motion. Especially in micromechanical parts, where only small forces are at play, a vanishing static friction can lead to hugely improved levels of efficiency.

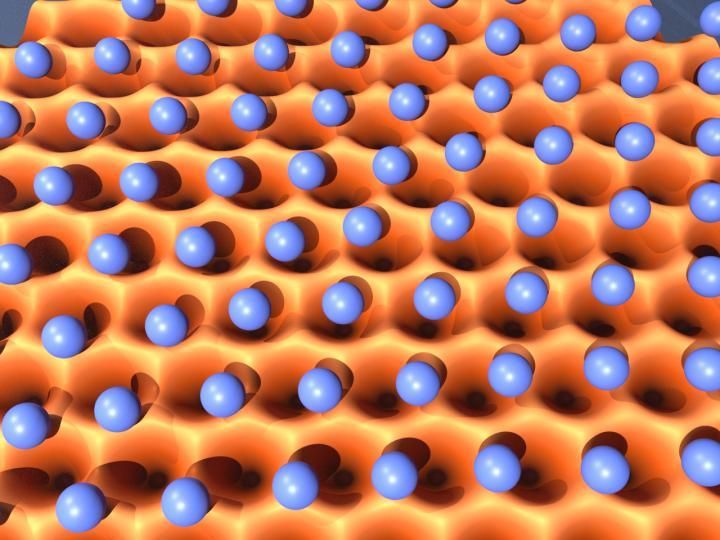

If the monolayer of a colloid crystal (blue pellets) slides over an optical grid (orange), friction can disappear entirely. This is because the particles avoid the recesses and move along the ridges of the optical grid.

Thorsten Brazda

To move a block of wood across a table one needs to pull it. When Leonardo da Vinci examined this deceptively simple relationship systematically more than 500 years ago, he discovered the basic laws of sliding friction. Since sliding friction usually generates heat, one must pull constantly on the chunk of wood to make up for frictional losses. However, to generate motion in the first place, it is not sliding friction but static friction that must be overcome. Static friction is typically larger than sliding friction and a result of the atomic structure of the contact surfaces locking into place. The surfaces can only free themselves and move against each other once the applied force has reached adequate levels.

Working with physicists from the Universities of Milan and Trieste, a University of Konstanz working group led by Professor Clemens Bechinger was able to conduct experiments and numerical simulations confirming a prediction made by the physicist Serge Aubry in the 1980s: He postulated that, if the lattice spacing between particles in one surface were to differ slightly from the lattice spacing in the other, friction between the two surfaces should disappear entirely. This is even expected to apply if the two surfaces are pressed together. In practical terms, this would mean that a randomly small force would suffice to move a chunk of wood weighing tons across a surface.

This effect can be observed particularly well in ideal contacts, where both surfaces are perfectly flat against each other. It is these kinds of surfaces that Clemens Bechinger and his team were able to create in a model system: Using laser beams and glass spheres in the mircometre range, so-called colloids, they were able to create a two-dimensional model of two surfaces rubbing against each other. Since the electrically charged spheres repel each other, they position themselves in a periodically ordered flat layer. This colloid monolayer forms one of the two surfaces. The researchers created the second surface beneath the layer of colloids by using three laser beams. As a result of their superposition a light crystal forms, which is a sort of optical egg crate with recesses and ridges. "In comparison to real surfaces, these optical surfaces have the added advantage of being entirely transparent, which means that we can directly observe the processes at work between them using a microscope", says Thorsten Brazda, the doctoral researcher who conducted the experiments in Bechinger's group for his doctoral thesis.

While Aubry restricted his prediction to one-dimensional contacts at zero-point temperatures, the research collaboration was able to prove that extended, two-dimensional contacts at room temperature can also be put in motion without static friction. "We were able to turn Aubry's artificial one-dimensional set-up into a realistic situation and demonstrate that his idea remains valid in two-dimensional systems and at finite temperatures", Clemens Bechinger comments.

Observing particle movements directly also allowed the researchers to understand the disappearance of static friction between the colloid monolayer and the light crystal: It turns out that the colloidal monolayer twists ever so slightly in relation to the optical grid. That way, the particles do not lock on to the recesses of the substrate, which they would not find it easy to escape from. Instead, some of them position themselves around the ridges. If external force is applied, these particles do not have to escape from the recesses but are free to move straight away as soon as a minimum amount of force is exerted. Static friction disappears.

These results, which are in excellent agreement with the numerical simulations performed by the Italian team, show that static friction cannot only be suppressed, but also generated as desired if the contact pressure between the two surfaces is increased. This is important insofar as static friction - in contrast to sliding friction - is often a desired phenomenon. It enables us to grasp objects safely and ensures that wheels have sufficient grip. This way of varying static friction creates new opportunities for moving objects easily across surfaces and to lock them into place safely. This would be of immense advantage in micro- and nanomechanical gearboxes or couplings, since, here, typically only very small forces are at play.