Einstein researchers find molecular structure of key fluorescent proteins

Scientists at Albert Einstein College of medicine of Yeshiva University have determined the crystal structures of two key fluorescent proteins – one blue, one red – used to "light up" molecules in cells. That finding has allowed them to propose a chemical mechanism by which the red color in fluorescent proteins is formed from blue. With this information, the researchers now have the first roadmap for rationally designing new and differently colored fluorescent proteins to illuminate the structures and processes in living cells. Such colored probes could provide a window, for example, into how biological processes in normal cells differ from those in cancer cells. Their study appears in chemistry & Biology.

This advance will expand the imaging revolution that began with a protein found in jellyfish. In 1992, researchers reported that the gene for green fluorescent protein (GFP) could be fused to any gene in a living cell. When the targeted gene is expressed, a "fusion protein" (consisting of the targeted gene's protein plus GFP) is formed. This fusion protein exhibits bright green fluorescence when exposed to blue light.

Thanks to GFP, scientists had a green imaging probe offering unprecedented access to the internal workings of living cells. They were able to use high-resolution light (optical) microscopes to observe the activation of genes of interest and to quantify and track newly expressed proteins as they perform their functions in living cells.

Many more fluorescent proteins of various colors were later found in other marine organisms such as corals. But the molecular nature of these colors remained a mystery, hindering the development of new imaging probes. Scientists seeking new fluorescent probes first had to fuse the genes for known fluorescent proteins to bacteria; then they exposed millions of these microorganisms to radiation, in hopes of producing random genetic mutations that lead to new and useful fluorescent proteins. The discovery by Einstein researchers will allow fluorescent proteins to be created in a much more systematic and rational way.

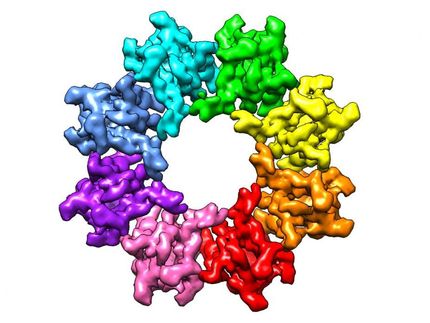

"Knowing the molecular structures of the chromophores – the part of fluorescent protein molecules that gives them their color – we can now do hypothesis-based designing of new probes, instead of relying on random mutations," says principal investigator Vladislav Verkhusha, Ph.D., associate professor of anatomy and structural biology and member of the Gruss Lipper Biophotonics Center at Einstein.

"In other words," says Dr. Verkhusha, "if we now change this or that fluorescent protein molecule in a certain way, we can predict that the change will yield a new protein that has a particular fluorescent color or other property that we are interested in." Using this new information, Dr. Verkhusha's laboratory has already designed a variety of new fluorescent proteins that can glow in colors ranging from blue to far-red.

Since researchers can now follow only two or three proteins at a time, an expanded fluorescent protein palette would be a big help. "To understand many cellular functions, you would like to follow dozens of different proteins, so the more colors we can develop, the better," says study co-author Steven C. Almo, Ph.D., professor of biochemistry and of physiology & biophysics at Einstein. He is an expert in x-ray crystallography, a method that determines the arrangement of atoms within a protein by striking the protein crystal with a beam of x rays.

Original publication: "Structural characterization of acylimine-containing blue and red chromophores in mTagBFP and TagRFP fluorescent proteins"; Chemistry & Biology 2010.

Most read news

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Pilot study successfully uses DNA sequencing to diagnose brain infections