World's first video recording of a space-time crystal

Periodic pattern consisting of magnons is formed at room temperature

A German-Polish research team has succeeded in creating a micrometer-sized space-time crystal consisting of magnons at room temperature. With the help of the scanning transmission X-ray microscope MAXYMUS at Bessy II at Helmholtz Zentrum Berlin, they were able to film the recurring periodic magnetization structure in a crystal. Published in the Physical Review Letters, the research project was a collaboration between scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems (MPI-IS) in Stuttgart, Germany, the Adam Mickiewicz University and the Polish Academy of Sciences in Poznań in Poland.

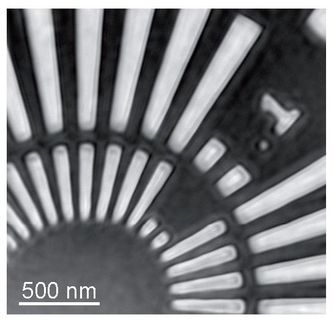

The upper grayscale image shows a snapshot of the time resolved X-ray microscopy of the magnonic space-time-crystal. Due to its interactions with other magnons, ultra-short spin waves emerge, which are depicted in the lower image.

Max-Planck-Institut für Intelligente Systeme

Order in space and a periodicity in time

A crystal is a solid whose atoms or molecules are regularly arranged in a particular structure. If one looks at the arrangement with a microscope, one discovers an atom or a molecule always at the same intervals. It is similar with space-time crystals: however, the recurring structure exists not only in space, but also in time. The smallest components are constantly in motion until, after a certain period, they arrange again into the original pattern.

In 2012, the Nobel Prize winner in physics Frank Wilczek discovered the symmetry of matter in time. He is considered the discoverer of these so-called time crystals, although as a theorist he predicted them only hypothetically. Since then, several scientists have searched for materials in which the phenomenon is observed. The fact that space-time crystals actually exist was first confirmed in 2017. However, the structures were only a few nanometers in size and formed only at very cold temperatures below -250 degrees Celsius. The fact that the German-Polish scientists have now succeeded in imaging relatively large space-time crystals of a few micrometers in a video at room temperature is therefore considered groundbreaking. But also because they were able to show that their space-time crystal, which consists of magnons, can interact with other magnons that encounter it.

An exceptional experiment succeeded

"We took the regularly recurring pattern of magnons in space and time, sent more magnons in, and they eventually scattered. Thus, we were able to show that the time crystal can interact with other quasiparticles. No one has yet been able to show this directly in an experiment, let alone in a video," says Nick Träger, a doctoral student at MPI-IS who, together with Pawel Gruszecki, is first author of the publication.

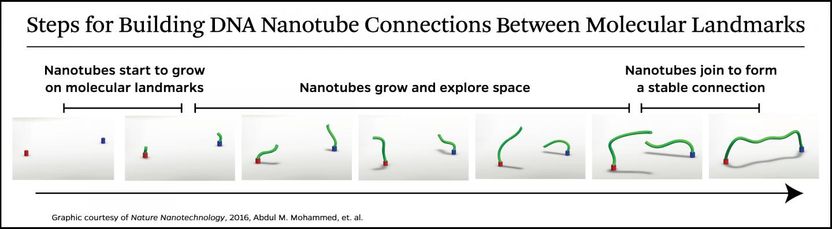

In their experiment, Gruszecki and Träger placed a strip of magnetic material on a microscopic antenna through which they sent a radio-frequency current. This microwave field triggered an oscillating magnetic field, a source of energy that stimulated the magnons in the strip – the quasiparticle of a spin wave. Magnetic waves migrated into the strip from left and right, spontaneously condensing into a recurring pattern in space and time. Unlike trivial standing waves, this pattern was formed before the two converging waves could even meet and interfere. The pattern, which regularly disappears and reappears on its own, must therefore be a quantum effect.

Gisela Schütz, Director at MPI-IS who heads the Modern Magnetic Systems Department, points out the uniqueness of the X-ray camera: "Not only can it make the wavefronts visible with very high resolution, which is 20 times better than the best light microscope. It can even do so at up to 40 billion frames per second and with extremely high sensitivity to magnetic phenomena as well."

"We were able to show that such space-time crystals are much more robust and widespread than first thought," says Pawel Gruszecki, a scientist at the Faculty of Physics of the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań. "Our crystal condenses at room temperature and particles can interact with it – unlike in an isolated system. Moreover, it has reached a size that could be used to do something with this magnonic space-time crystal. This may result in many potential applications."

Joachim Gräfe, former research group leader in the Department of Modern Magnetic Systems at MPI-IS and last author of the publication, agrees with his colleagues and concludes: "Classical crystals have a very broad field of applications. Now, if crystals can interact not only in space but also in time, we add another dimension of possible applications. The potential for communication, radar or imaging technology is huge."