New rapid test could detect coronavirus and flu simultaneously

It could also detect other diseases and different coronavirus variants

Researchers from the University of Basel and the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI have developed a rapid test for Covid-19 with a novel functional principle. Although it requires further testing and improvements, the initial results are promising: As well as determining whether a Covid-19 infection is present, the test also promises to provide information on the status of the disease. It could also detect other diseases and different coronavirus variants.

Symbolic image

pixabay.com/Unsplash

One major shortcoming of rapid antigen tests is their lack of reliability. A study by the German Paul Ehrlich Institute showed that, of the 122 test kits that were tested, one-fifth didn’t even achieve the minimum requirement of identifying 75 percent of the test subjects carrying a high viral load as being positive for coronavirus. Another drawback is that these tests only indicate whether the subject has the disease or not, without providing any insight into the course of the infection or the immune reaction of the test subjects.

Now, a new test developed at PSI relies on a different principle than the antigen tests: Instead of detecting components of the virus directly, it detects the antibodies that the immune system produces in response to the infection. This test promises to bring substantially more predictive power to rapid testing and can be used to simultaneously identify a variety of pathogens, such as those responsible for the flu. “Thus, it also provides more data than previous rapid antibody tests that are used to determine whether someone has already had a coronavirus infection,” says Dr. Yasin Ekinci, head of the Laboratory for X-ray Nanoscience and Technologies at PSI, who oversaw the project.

Multifunctional microstructure

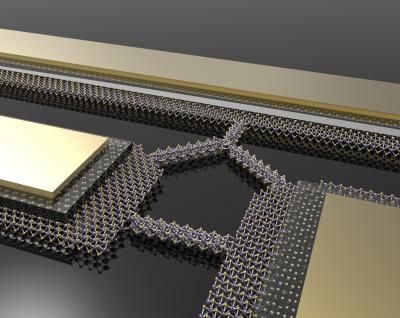

The central building block of the test is a small rectangular plate of Plexiglas made up of two layers, between which run three uniform, parallel channels with a special structure: At the inlet, each of them is 300 micrometers (0.3 millimeters) wide and 3.4 micrometers high. At the outlet, the channels are five times as wide but only 0.8 micrometer high — and they become even thinner and narrower in-between.

“Among other things, this special channel structure ensures a strong capillary effect that sucks liquid from one end of the Plexiglas plate to the other,” explains Thomas Mortelmans, first author of the study. Mortelmans is a doctoral student at the Swiss Nanoscience Institute and carried out his research at PSI.

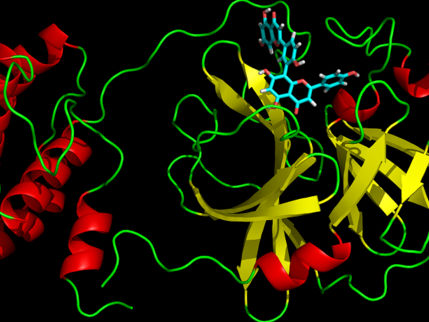

As Mortelmans explains, the test requires a patient to visit a doctor or a test center. There, a small drop of blood is extracted via a finger prick, as in a blood sugar test, and then mixed with a liquid in which special artificial nanoparticles are suspended. The surface of these particles has the same structure as the notorious spike proteins of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which human antibodies dock to when fighting the disease. In addition, small fluorescent particles are added that attach themselves to antibodies.

In the event that the drop of blood contains antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, the fluorescent particles first attach themselves to the antibodies; together, they then bind to the virus-like structures of the significantly larger nanoparticles. The drop of blood is subsequently placed at the inlet of the tiny channels and is drawn in by capillary forces. At a very narrow, predefined point known as the “capture region,” the nanoparticles get stuck along with any antibodies that may be present — as well as their glowing appendages.

If the plate is placed under a fluorescence microscope, a visible light signal is emitted. The brighter the signal, the more SARS-CoV-2 antibodies the person has formed. In this way, the signal strength can be used to identify whether the immune system is reacting well, and a mild case can be expected — or whether it might be overreacting, which implies a risk of complications, as Mortelmans explains.

One rapid test with many possibilities

In addition, nanoparticles of different sizes and with different surface structures could be mixed into the drop of blood to enable simultaneous testing for other diseases. In the study, Mortelmans achieved this using particles with a surface corresponding to influenza A viruses, for example. The experiments had two spots in the capture region that provided information about an infection: one that lit up for Covid-19 and another for flu.

In addition, it is possible to identify different antibodies that the immune system produces at different stages of the disease. For example, the test could use a green fluorescent particles that only attach to antibodies that appear in the early phase of the infection, and red fluorescent particles for antibodies that are produced by the immune system at later stages. “The test can be extended in many ways,” says Mortelmans. “We could, for example, test 10 different diseases at once without any problems and use four colors as well.”

For their study, the researchers tried their new test on 29 blood samples — 19 of which came from infected individuals and 10 from non-infected individuals. With the exception of one false-negative case, the test was always correct. This too was identified in the follow-up test. “Of course, we need to do a lot more testing to make a solid statement about reliability. But it is very promising,” says Ekinci. As yet, it is not possible to predict when the test will be ready for the market.

Further development will aim to make the test even faster and easier to carry out. Testing currently takes between 10 and 30 minutes, but the researchers say it could also be carried out in two minutes — and the test is currently being optimized with that aim in mind. Moreover, it may one day be possible to perform the test using saliva instead of blood and to read the result with a mobile phone instead of a microscope.