A new method for studying ribosome function

UIC scientists use native chemical ligation to fuse peptides to tRNAs

Inside tiny cellular machines called ribosomes, chains of genetic material called messenger RNAs (mRNAs) are matched with the corresponding transfer RNAs (tRNAs) to create sequences of amino acids that exit the ribosome as proteins. Unfinished proteins are called nascent chainsm and they are left attached to the ribosome.

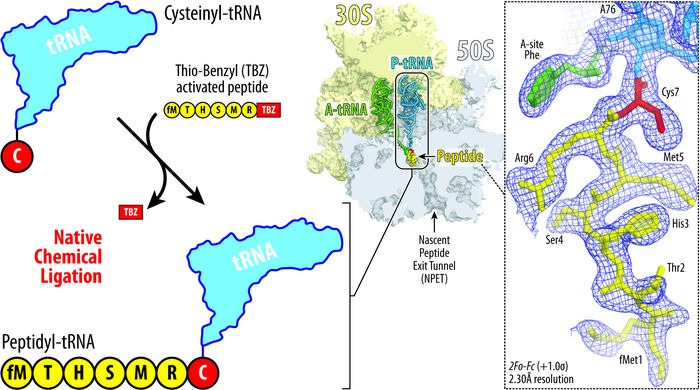

Illustration showing the principle of native chemical ligation approach developed by Syroegin, et al. Addition of the cysteine amino acid (red) to tRNA (blue, top left) allows for the tRNA to fuse to a peptide (yellow, lower left). The resulting ribosome structure (middle) and the captured electron density maps for the peptidyl-tRNA inside the ribosome (right) were obtained by X-ray crystallography in the UIC experiments.

Syroegin, et al.

Scientists know that some of these nascent chains can regulate the activity of the ribosome and that the nascent chains can sometimes interfere with antibiotics — many of which work by targeting bacterial ribosome activity. Scientists do not know why this happens, mainly because it is hard to visualize what the ribosome-peptide-drug interactions look like while the unfinished proteins are still tethered to the ribosome.

Now, scientists at the University of Illinois Chicago are the first to report a method for stable attachment of peptides to tRNAs, which has allowed them to gain new fundamental insights into ribosome function by determining the atomic-level structures of ribosomes and the shapes that these peptides take inside the ribosome.

“The challenge has been to see up close the structure of the ribosome and the exit tunnel in the presence of the nascent peptides because, in nature, the ribosome is very quick for us to capture images or conduct experiments,” said Yury Polikanov, associate professor in the biological sciences department at the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. “Until the advent of this new method, we’ve essentially been blinded from seeing what is happening in the active site of the ribosome at this critical moment in time.”

Polikanov and his colleague Egor Syroegin, a PhD candidate in biological sciences at UIC, used a method called native chemical ligation to fuse custom peptides with the tRNA to yield what is called a peptidyl-tRNA.

“Obtaining tRNA molecules linked to peptides, similar to those inside the ribosome during protein synthesis, has remained a dream of many researchers in the field for almost two decades,” Polikanov said. “This has been extremely challenging because there are no enzymes that can directly attach peptides to a tRNA.”

“The method has been used for a long time in chemistry, but it has never been applied in this way. It’s mimicking nature, basically, and with our advanced imaging experience, we are now seeing how nature works at a high resolution,” Syroegin said.

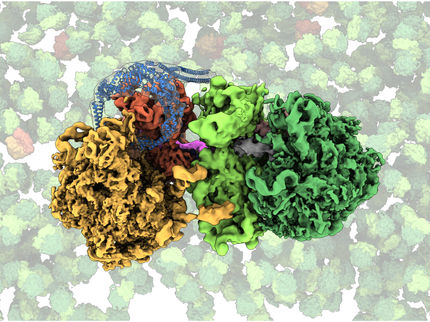

With this new approach, Polikanov and Syroegin determined a set of high-resolution structures of the ribosome carrying peptidyl-tRNAs of various lengths.

Detailed analysis of these structures provides new and surprising insights into the mechanism of the ribosome’s catalytic center and answered several long-standing fundamental questions in the ribosome field, Polikanov said.

“We saw that depending on the sequence, different peptides can form different shapes or folds within the ribosomal tunnel, and we can synthesize different peptides of different sequences and then follow their shape very precisely, because of the high resolution of our structures,” Syroegin said. “So now, we can very confidently say that ‘these peptides, of this sequence, have this shape’ or ‘another peptide has another shape.’ That’s important because nascent peptide folding determines whether drugs would arrest ribosome or not.”

“This method opens countless avenues for structural and functional studies aimed at understanding the mechanisms of ribosome functioning, as well as sequence-specific ribosome stalling induced by certain antibiotics,” Polikanov said.

Original publication

"Insights into the ribosome function from the structures of non-arrested ribosome–nascent chain complexes"; Nature Chemistry.