New imaging method sheds light on cell growth

University of Illinois researchers are giving a light answer to the heavy question of cell growth.

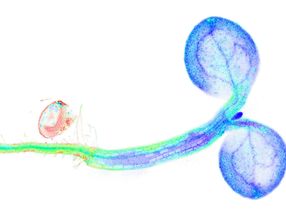

Illinois researchers developed a novel imaging technique, spatial light interference microscopy (SLIM), that can quantitatively measure cell mass with light.

Quantitative Light Imaging Laboratory

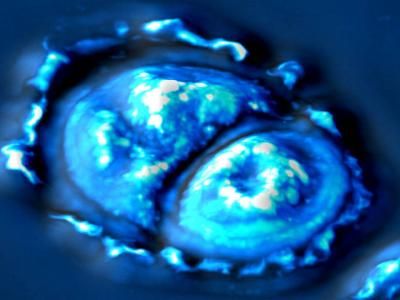

Led by electrical and computer engineering professor Gabriel Popescu, the research team developed a new imaging method called spatial light interference microscopy (SLIM) that can measure cell mass using two beams of light. Described in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the SLIM technique offers new insight into the much-debated problem of whether cells grow at a constant rate or exponentially.

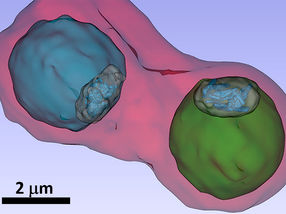

SLIM is extremely sensitive, quantitatively measuring mass with femtogram accuracy. By comparison, a micron-sized droplet of water weighs 1,000 femtograms. It can measure the growth of a single cell, and even mass transport within the cell. Yet, the technique is broadly applicable.

"A significant advantage over existing methods is that we can measure all types of cells – bacteria, mammalian cells, adherent cells, nonadherent cells, single cells and populations," said Mustafa Mir, a graduate student and a first author of the paper. "And all this while maintaining the sensitivity and the quantitative information that we get."

Unlike most other cell-imaging techniques, SLIM – a combination of phase-contrast microscopy and holography – does not need staining or any other special preparation. Because it is completely non-invasive, the researchers can study cells as they go about their natural functions. It uses white light and can be combined with more traditional microscopy techniques, such as fluorescence, to monitor cells as they grow.

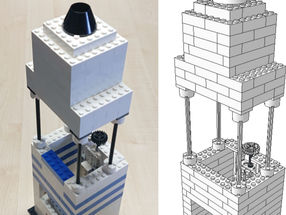

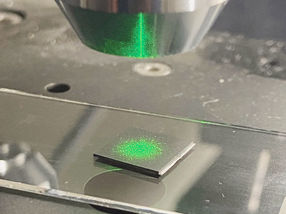

"We were able to combine more traditional methods with our method because this is just an add-on module to a commercial microscope," Mir said. "Biologists can use all their old tricks and just add our module on top."

Because of SLIM's sensitivity, the researchers could monitor cells' growth through different phases of the cell cycle. They found that mammalian cells show clear exponential growth only during the G2 phase of the cell cycle, after the DNA replicates and before the cell divides. This information has great implications not only for basic biology, but also for diagnostics, drug development and tissue engineering.

The researchers hope to apply their new knowledge of cell growth to different disease models. For example, they plan to use SLIM to see how growth varies between normal cells and cancer cells, and the effects of treatments on the growth rate.

Popescu, a member of the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology at the U. of I., is establishing SLIM as a shared resource on the Illinois campus, hoping to harness its flexibility for basic and clinical research in a number of areas.

"It could be used in many applications in both life sciences and materials science," said Popescu, who also is a professor of physics and of bioengineering. "The interferometric information can translate to the topography of silicon wafers or semiconductors. It's like an iPad – we have the hardware, and there are a number of different applications dedicated to specific problems of interest to different labs."

Original publication

Most read news

Original publication

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

![[Fe]-hydrogenase catalysis visualized using para-hydrogen-enhanced nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy](https://img.chemie.de/Portal/News/675fd46b9b54f_sBuG8s4sS.png?tr=w-712,h-534,cm-extract,x-0,y-16:n-xl)