X-ray laser reveals chemical reaction

What happens when a chemical bond is broken? That question was recently answered with the help of a so-called free electron x-ray laser, which makes it possible to follow in real time how bindings in a molecule are changed and broken. The study, published in Science, found, among other things, evidence of a much-discussed intermediate state before molecules bind to or leave a metal surface. The possibility of monitoring at the molecular level how the electron structure changes in a chemical reaction creates entirely new opportunities for investigating and understanding key chemical processes in detail.

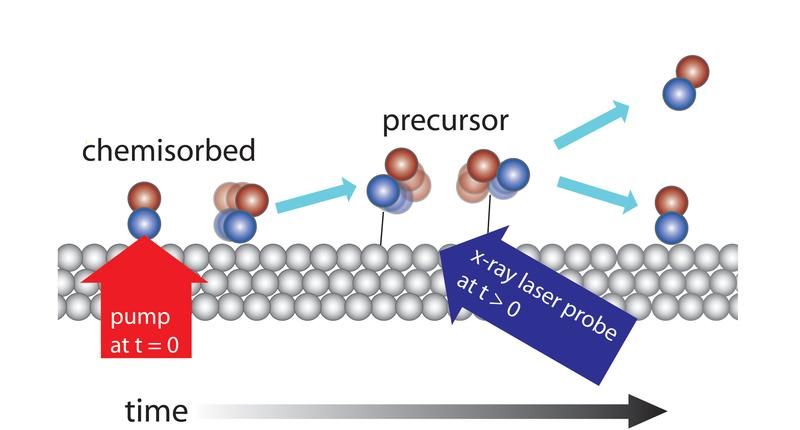

Caption: The x-ray laser investigates the change in the electron structure when CO molecules desorb from a metal surface of ruthenium. Roughly 30% of the molecules are pumped up with the aid of a femtosecond of optic laser from the surface-bonded (“chemisorbed”) state to a transient intermediate state (“precursor”) where they interact faintly with the surface. By examining the molecules with the x-ray laser with varying delay periods, it is possible to show that the time scale for achieving the precursor state is a few picoseconds and that they exist there for a few tens of picoseconds before either leaving the surface entirely or returning to the surface.

Stockholm University

“To identify and characterize short-lived intermediate states in chemical reactions on the surface of metals has long been a dream,” says Henrik Öström at the Department of Physics, Stockholm University, who is part of the international research team that carried out the study. “With the new free electron x-ray laser at SLAC, we have shown that dreams can become reality and managed to identify a short-lived intermediate state when the bindings of CO molecules to a metal surface are broken or created.

SLAC (Stanford Linear Accelerator Center) was long a flagship of particle physics, where electrons were accelerated to nearly the speed of light in a three-kilometer-long linear accelerator. Now the accelerator has been rebuilt to generate, instead, powerful ultra-short (10-100 femtosecond) pulses of x-ray beams with a wavelength that makes it possible to examine the surroundings of a molecule down to the level of an individual atom. The pulses are sufficiently short to provide a snapshot of the electron distribution around the atom. By varying the delay between the start of a reaction and when the distribution of electrons is monitored with the x-ray pulse, these scientists can create a suspended-time image of changes in the course of the reaction.

“A first challenge was whether the incredibly powerful pulse would destroy the sample,” explains Anders Nilsson, a professor of synchrotron-light physics at SLAC and an adjunct professor at Stockholm University. “However, it turned out to be entirely possible to adjust the experiment in a way that enabled us to make our measurements.”

In the experiment, CO molecules were dosed onto a metal surface of ruthenium, which is used in automobile catalytic converters, for instance. CO binds strongly to the surface but can be made to let go by heating up the surface, which was done with a pulse from an optical laser. By starting the reaction for all the molecules at the same time, the team got a sufficient number of molecules to simultaneously enter a state where they have almost let go of the surface but still have a weak binding to it. From this short-lived state, the molecules can then continue out into a gas phase or renew their bond when the surface cools down again.

“Scientists have long speculated whether such a state, a so-called ‘precursor,’ exists. The new experiment is the first to directly show its existence,” says Lars G. M. Pettersson at the Department of Physic, Stockholm University. These studies will not go on to more complex reactions of interest to the field of synthetic fuels, among other applications.

Most read news

Original publication

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.