Researchers develop key power-splitting component for terahertz waves

One of the most basic components of any communications network is a power splitter that allows a signal to be sent to multiple users and devices. Researchers from Brown University have now developed just such a device for terahertz radiation -- a range of frequencies that may one day enable data transfer up to 100 times faster than current cellular and Wi-Fi networks.

One of the most basic components of any communications network is a power splitter that allows a signal to be sent to multiple users and devices. Researchers from Brown University have now developed just such a device for terahertz radiation -- a range of frequencies that may one day enable data transfer up to 100 times faster than current cellular and Wi-Fi networks.

Mittleman lab / Brown University

"One of the big thrusts in terahertz technology is wireless communications," said Kimberly Reichel, a post-doctoral researcher in Brown's School of Engineering who led the device's development. "We believe this is the first demonstration of a variable broadbrand power splitter for terahertz, which would be a fundamental device for use in a terahertz network."

The device could have numerous applications, including as a component in terahertz routers that would send data packets to multiple computers, just like the routers in current Wi-Fi networks.

Today's cellular and Wi-Fi networks rely on microwaves, but the amount of data that can travel on microwaves is limited by frequency. Terahertz waves (which span from about 100 to 10,000 GHz on the electromagnetic spectrum) have a higher frequency and therefore the potential to carry much more data. Until recently, however, terahertz hasn't received much attention from scientists and researchers, so many of the basic components for a terahertz communications network simply don't exist.

Daniel Mittleman, a professor in Brown's School of Engineering, has been working to develop some of those key components. His lab recently developed the first system for terahertz multiplexing and demultiplexing -- a method of sending multiple signals through a single medium and then separating them back out on the other side. Mittleman's lab has also produced a new type of lens for focusing terahertz waves.

Each of the components Mittleman has developed makes use of parallel-plate waveguides -- metal sheets that can constrain terahertz waves and guide them in particular directions.

"We're developing a family of waveguide tools that could be integrated to create the appropriate signal processing that one would need to do networking," said Mittleman, who was a co-author on the new paper along with Reichel and Brown research professor Rajind Mendis. "The power splitter is another member of that family."

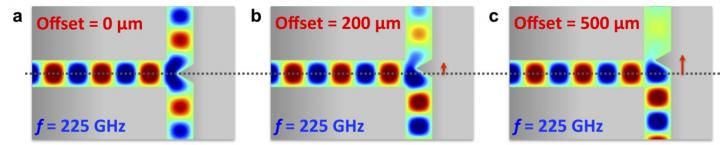

The new device consists of several waveguides arranged to form a T-junction. Signal going into the leg of the T is split by a triangular septum at the junction, sending a portion of the signal down each of the two arms. The septum's triangular shape minimizes the amount of radiation that reflects back down the leg of the T, reducing signal loss. The septum can be moved right or left in order to vary the amount of power that is sent down either arm.

"We can go from an equal 50/50 split up to a 95/5 split, which is quite a range," Reichel said.

For this proof-of-concept device, the septum is manipulated manually, but Mittleman says that process could easily be motorized to enable dynamic switching of power output to each channel. That could enable the device to be incorporated in a terahertz router.

"It's reasonable to think that we could operate this at sub-millisecond timescales, which would be fast enough to do data packet switching," Mittleman said. "So this is a component that could be used to enable routing in the manner of the microwave routers we use today."

The researchers plan to continue to work with the new device. A next step, they said, would be to start testing error rates in data streams sent through the device.

"The goal of this work was to demonstrate that you can do variable power switching with a parallel-plate waveguide architecture," Mittleman said. "We wanted to demonstrate the basic physics and then refine the design."