Illuminating the contacts

The development of super resolution microscopy has revolutionised how scientists view and understand the inner workings of the cell. Just as advances in satellite camera technology gave rise to highly detailed maps of the world, so too has super-resolution microscopy allowed researchers to build detailed maps of individual cells. Such is the detail, that not only is the location of individual protein-based machines achievable, but these machines can be broken down into their parts, and the position and orientation of these parts, mapped out as well.

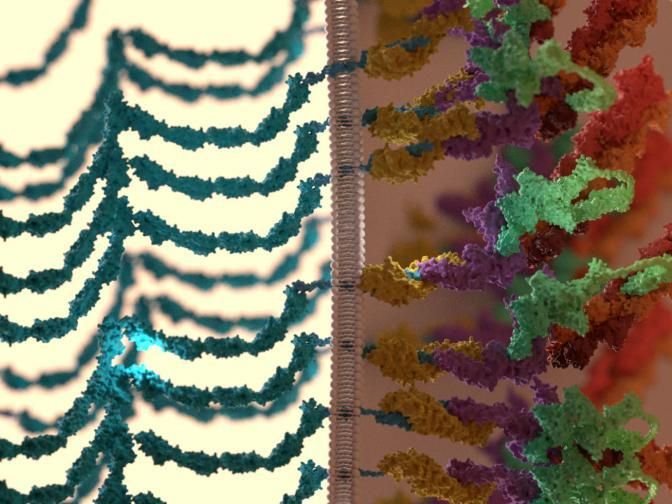

Figure: Intracellular adherens junctions are initiated by interactions between extracellular domains of membrane-bound cadherins (shown in blue) on adjacent cells. On the intracellular side, the cadherins are linked to the actin cytoskeleton via a cytoplasmic plaque, which is chiefly constituted by catenin proteins: beta-catenins (yellow) and alpha-catenins (purple). The plaque also contains another prominent protein called vinculin (green) that primarily responds to mechanical and biochemical signals by extending in length, and in doing so, couples the cadherin-catenin complexes to the actin cytoskeleton (red).

Mechanobiology Institute, Singapore National University of Singapore

In the human body, cells rarely function in isolation. Instead they exist as part of multicellular communities that make up tissues and organs. To ensure the tissue functions correctly, individual cells must remain in physical contact with their surrounding cells. When cells are unable to maintain this contact, devastating diseases may arise, cancer being one of the most dreaded examples.

Cell-cell adhesion sites are found at specific regions of the cell periphery. Although many of the protein parts that make up these adhesion sites were known, scientists had yet to determine how each part fit together to make the overall machine. This was because the building blocks of these machines were both far too small for traditional light microscopes, and far too diverse for electron microscopes.

One of the main protein parts in these machines are the 'cadherin' proteins. The cadherin of one cell extends outside the cell, and interact with cadherin of another cell. On the inside of the cell, cadherin binds to 'adaptor' proteins, which essentially connect the cadherin to a network of protein filaments known as the cytoskeleton. By forging these robust links, cadherin adhesions not only connect neighbouring cells but allow cells to coordinate their movements, maintain tissue integrity, and relay a myriad of signals important for proper tissue functions.

Super-resolution imaging reveals multi-layered organisation of cadherin-based adhesions

With super-resolution microscopy at their disposal, an international research team led by Assistant Professor Pakorn (Tony) Kanchanawong from the Mechanobiology Institute, Singapore (MBI) at the National University of Singapore (NUS) and the Department of Biomedical Engineering at NUS, as well as Dr Cristina Bertocchi, Research Fellow at MBI, has revealed, for the first time, how the cadherin-based cell-cell contacts are organised. At the heart of the study is a 'map' of how the parts are pieced together into a sophisticated nanoscale cell-cell adhesion machine.

Here, the researchers 'mapped' the position and orientation of the protein building blocks of cadherin adhesions. They noted a striking degree of compartmentalisation in the organisation of the protein machinery where components were arranged into multiple layers. The cadherin and the cytoskeleton compartments appeared to be separated by an 'interface layer', which contains vinculin, a stretchable protein which has long been implicated in the cell's ability to sense mechanical force. In this case, Dr Bertocchi observed that vinculin could undergo a dramatic shape-shifting transformation, whereby it would switch from a compact shape to a highly elongated form. This elongated form was sufficient to stretch over a distance of 30 nanometres or more, which was the same distance that cadherin was separated from the cytoskeleton. In a nutshell, vinculin could serve as a bridge to link between the cadherin and actin layers.

Further investigation of this structure highlighted that the shape of vinculin (stretched or compact) was determined by both mechanical tension and biochemical signal inputs. Therefore, the ability of vinculin to selectively engage with a highly dynamic actin cytoskeleton highlights vinculin's role in fine-tuning the mechanical properties of cell-cell contacts in response to varying inputs from the extracellular environment.

The ability to observe, under a microscope, molecular machines such as the cadherin based cell-cell adhesion highlights the power of super resolution microscopy. In this case, the protein parts that make up the cell-cell adhesion have been mapped out, allowing researchers to better understand how cell-cell contacts are formed, maintained, regulated and reinforced to perform vital biological functions.