Better Imaging Using Sound

A microscopy technique in which sound is measured instead of light.

Individual molecules cannot be photographed – if you wish to visualise objects that are smaller than the wavelength of light, you'll need a few special tricks up your sleeve. You can use electron microscopes for example, or determine the position of specific fluorescent molecules by taking a large number of images one after the other.

After years of research, a team from the Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Information Technology at TU Wien was able to present a new microscopy technique, which can be used to visualise individual molecules and even reliably identify them. The molecules are placed on a tiny membrane and irradiated with a laser, whereby the way in which the vibration behaviour of the membrane changes is measured. Thus, the key measurement variable is not light, but rather a mechanical vibration, i.e. sound.

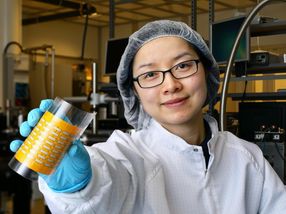

Taking a picture of single molecules, using sound

TU Wien

The molecule on the membrane

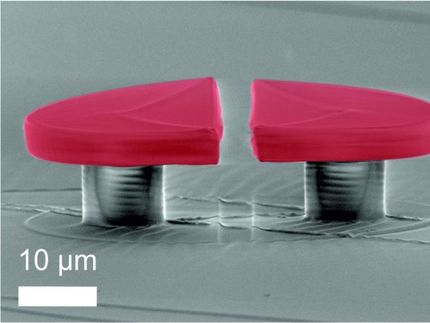

Prof. Silvan Schmid from the Institute of Sensor and Actuator Systems at TU Wien is working on the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and tiny mechanical structures. "We place individual molecules on very specific, extremely thin membranes", he explains. "The membrane is then scanned by a laser beam."

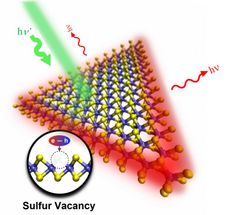

The wavelength of the laser beam is selected so that it has a particularly strong interaction with the molecule that is being searched for. If the laser beam comes into contact with the molecule, it absorbs energy and heats up the area of the membrane surrounding it. This temperature increase in turn detunes the vibration frequency.

"Think of it as a small drum", explains Silvan Schmid. "When the drum skin heats up, the noise that the drum makes also changes. The same thing is happening with our micro membranes."

The membrane vibrates at a frequency of around 20 Kilohertz – this corresponds to a very high tone in a frequency range that children are usually still able to hear (at least to some extent). The noise produced by the membrane in nanomechanical absorption microscopy is, however, much too quiet to be noticeable. It is measured using optical sensors.

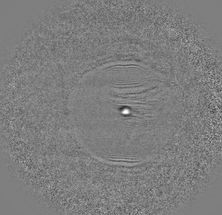

If the entire membrane is illuminated point-by-point with the laser and the acoustic "detuning" of the membrane is measured each time, you can calculate where a molecule is located, allowing an image with high contrast to be created. "We have applied this technique to fluorophores, in other words fluorescent molecules, which can also be visualised using other techniques. This allowed us to demonstrate that our vibration imaging method really does work", says Silvan Schmid. "Our technique can, however, also be applied to other molecules. All you need to do is select the right wavelength for the laser beam."

It all depends on the membrane

The deciding factor in the success of the new technique was the creation of suitable membranes. "We needed a material whose vibration behaviour changed as clearly as possible when heated locally by the individual molecules", says Silvan Schmid. "We finally achieved this using silicon nitride membranes with a surface made from silicon oxide."

Silvan Schmid's research team worked on this project together with the biophysics research group led by Prof. Gerhard Schütz (also at TU Wien), which specialises in particularly challenging microscopy techniques.

There are a wide range of possible applications for the new technology: "Our new technique produces a strong signal, which makes it appealing to many industries. It can be used to locate and analyse individual molecules, and to create detectors for tiny amounts of material. It can also be used in solid state research, for instance to measure electronic vibrations in nanoantennae", concludes Silvan Schmid.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.