CU scientists create world's thinnest balloon: Just one atom thick

Using a lump of Graphite, a piece of Scotch tape and a silicon wafer, Cornell researchers have created a balloonlike membrane that is just one atom thick - but strong enough to contain gases under several atmospheres of pressure without popping. And unlike your average party balloon - or even a thick, sturdy glass container - the membrane is ultra-strong, leak-proof and impermeable to even nimble helium atoms.

The research, by former Cornell graduate student Scott Bunch (now an assistant professor at the University of Colorado), Cornell professor of physics Paul McEuen and Cornell colleagues, could lead to a variety of new technologies - from novel ways to image biological materials in solution to techniques for studying the movement of atoms or ions through microscopic holes. The work was conducted at the National Science Foundation-supported Cornell Center for Materials Research and published in the journal Nano Letters.

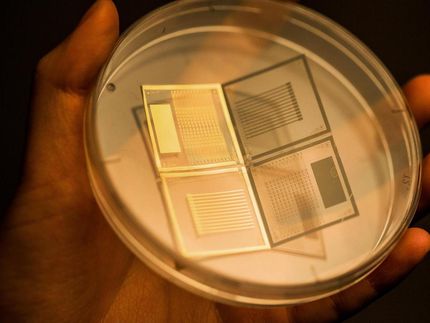

Scientists discovered several years ago that isolating graphene sheets is as simple as sticking Scotch tape to pure graphite, then peeling it back and re-sticking it to a silicone dioxide wafer. Peeled back from the wafer, the tape leaves a residue of graphite anywhere from one to a dozen layers thick - and from there researchers can easily identify areas of single-layer-thick graphene.

To test the material's elasticity, the Cornell team deposited graphene on a wafer etched with holes, trapping gas inside graphene-sealed microchambers. They then created a pressure differential between the gas inside and outside the microchamber. With a tapping atomic force microscope, which measures the amount of deflecting force a tiny cantilever experiences as it scans nanometers over the membrane's surface, the researchers watched the graphene as it bulged in or out in response to pressure changes up to several atmospheres without breaking.

They also turned the membrane into a tiny drum, measuring its oscillation frequency at different pressures. They found that helium stays trapped behind a wall of graphene - again, even under several atmospheres of pressure.

"When you work the numbers, you would expect that nothing would go through, so it's not a scientific surprise," said McEuen. "But it does tell you that the membrane is perfect" - since even an atom-sized hole would allow the helium to escape easily.

Such a membrane could have all kinds of uses, he added. It could form a barrier in an aquarium-like setup, for example, allowing scientists to image biological materials in solution through a nearly invisible wall without subjecting the microscope to the wet environment. Or, researchers could poke atomic-sized holes in the membrane and use the system to study how single atoms or ions pass through the opening.

Most read news

Other news from the department science

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.