Using mini colons to detect functional differences and weaknesses of colorectal cancer

Pooled in vitro and in vivo CRISPR-Cas9 screening identifies tumor suppressors in human colon organoids

One of the main features of colorectal cancer is that there are considerable differences between the tumors of individual patients - at genetic level and hence in terms of the response to treatment too. Researchers from the German Cancer Consortium (DKTK) have developed a method that allows these differences to be identified more effectively. They use mini colons grown in the laboratory for their studies that allow them to work under conditions that are as similar as possible to those found in patients. The scientists perform a large number of parallel experiments on these "organoids", which improves the comparability of the results. The DKTK is a consortium centered around the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) in Heidelberg, which has long-term collaborative partnerships with specialist oncological centers at universities across Germany.

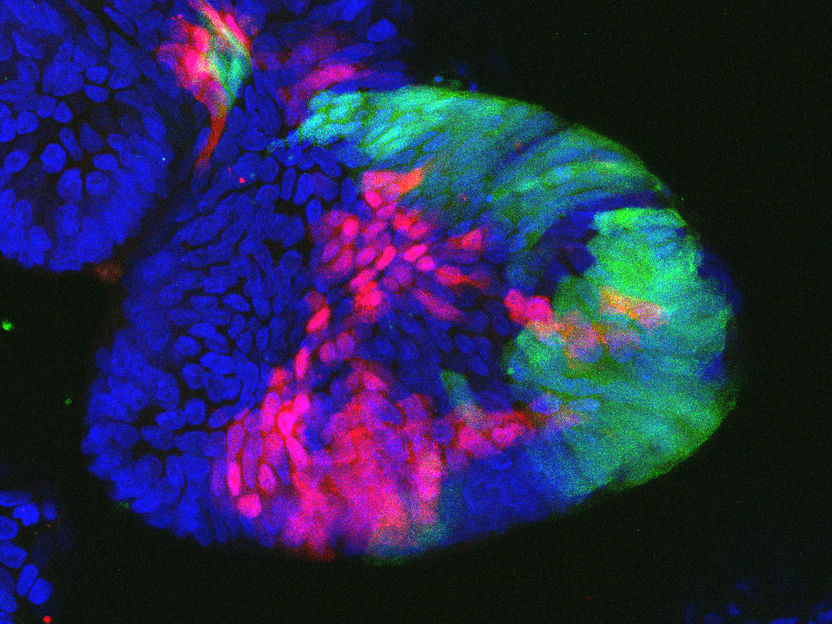

"Mini intestines" (colon organoids): After loss of the tumor suppressor gene cell regions are marked red and green.

Henner Farin / DKTK

To provide targeted treatment for cancer, the only way to achieve the hoped-for results is to ensure that our knowledge about the tumor is as precise as possible. In colorectal cancer, in particular, there are known to be considerable genetic differences, as a result of which the tumors of individual patients have highly diverse characteristics. These include whether there are promising starting points for treatment, which substances are most effective, and what treatment resistance there may be.

"Up to now, medical scientists have concentrated on isolating and culturing tumor cells to study the tumors of individual patients more closely," remarked DKTK researcher Henner Farin. "But that does not work for every tumor and it also results in cell lines that do not have very much in common with the original tumor." It is thus difficult to say anything about the individual characteristics of a tumor using these kinds of cell cultures.

Farin and his colleagues at the Georg Speyer Haus - Institute for Tumor Biology and Experimental Therapy in Frankfurt are therefore taking a different approach. Farin established a cell culture model that can be used to grow "mini colons" - known as organoids - in the laboratory. These organoids are three-dimensional cell cultures whose structure and essential functions are very similar to those of the organ on which they are based. "Organoids like these are used in pharmacology to test substances, for example," Farin explained. "We use them to examine the genetic differences between individual tumors in detail and to find out what that means in terms of their characteristics."

In the current study, the scientists used CRISPR/Cas9 technology to turn off tumor suppressor genes in the organoids. These genes are the cancer "brakes" that normally ensure that mutant cells die and tumors cannot develop in the first place. Loss of these tumor suppressor genes has a tumor-promoting effect. Instead of performing elaborate test series to examine the effect of the cancer brakes individually, the scientists in Farin's team create libraries that can be used to investigate the loss of a whole series of tumor suppressor genes at the same time.

Each cell has an individual DNA barcode that is read in parallel. This allows the researchers to identify which genetic mutations lead to cancer cells becoming resistant to a particular mode of treatment. "Comparing several pooled tumor suppressor genes together increases the throughput and ensures that all the genes can be studied under the same conditions and hence without bias," Farin explained.

In order not just to study the tumor suppressor genes in the Petri dish, the scientists carried out a further experiment in which they transplanted their organoids into mice. "We thus developed a model system that is as similar as possible to the situation in patients," Farin commented. The system can be used to establish whether the loss of tumor suppressor genes leads to a growth advantage for the cancer cells in living organisms too.

"In combination with the CRISPR/Cas9 libraries, the organoids provide us with a technology with which we can examine the patient-specific tumor features," Farin explained. "That allows us to identify the individual weaknesses of a tumor against which successful treatment can be directed." The organoid system can thus become an important tool for personalized medicine.

Original publication

Birgitta E. Michels, Mohammed H. Mosa, Barbara I. Streibl, Tianzuo Zhan, Constantin Menche, Khalil Abou-El-Ardat, Tahmineh Darvishi, Ewelina Członka, Sebastian Wagner, Jan Winter, Hind Medyouf, Michael Boutros und Henner F. Farin; "Pooled in vitro and in vivo CRISPR-Cas9 screening identifies tumor suppressors in human colon organoids"; Cell Stem Cell; 2020