Molecules have an orientation, and scientists have a new way to measure it

Molecular orientation is key to designing better materials

In some materials, the molecules line up in a regular, repeating pattern. In others, they all point in random directions. But in many advanced materials used in medicine, computer chip manufacturing and other industries, the molecules arrange themselves in complex patterns that dictate the material’s properties.

Symbolic image

Computer-generated image

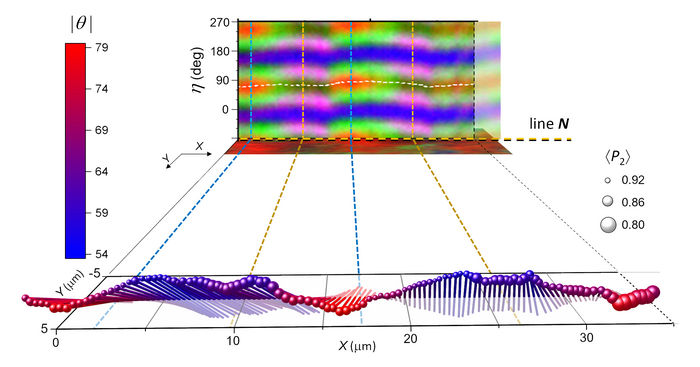

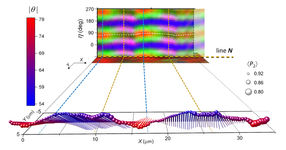

To advance materials science, researchers at NIST have developed a new way to measure the 3D orientation of molecules within a material made of components called polymers. In this illustration, the pinlike forms represent polymer chains, with the color indicating average angle off the vertical plane and the size of the pinhead representing the distribution of orientations around that average. The image in the background shows the raw data, which is produced by a method known as broadband coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering, or BCARS.

Y.J. Lee/NIST

Scientists haven’t had good ways to measure molecular orientation in three dimensions at a microscopic scale, leaving them in the dark about why some materials behave the way they do. Now, researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have measured the 3D orientation of the molecular building blocks of plastics, called polymers, observing details as small as 400 nanometers, or billionths of a meter, in size.

The measurements, described in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, show polymer chains twisting and undulating in complex and unexpected ways. The new measurements were made using a souped-up version of a technique called broadband coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering, or BCARS.

BCARS works by shining laser beams at a material, causing its molecules to vibrate and emit their own light in response. This technique, developed about a decade ago at NIST, is used to identify what a material is made of. To measure molecular orientation, NIST research chemist Young Jong Lee has added a system for controlling the polarization of the laser light and new mathematical methods for interpreting the BCARS signal.

Specifically, the new technique measures the average orientation of the polymer chains within 400-nanometer regions, along with the distribution of orientations around that average. These measurements will allow scientists to identify molecular orientation patterns that produce the mechanical, optical and electrical properties they seek.

“Understanding that structure/function relationship can really speed up the discovery process,” Lee said.

This will help researchers to optimize the materials used in medical devices such as arterial stents and artificial knees. The orientation of the molecules on the surface of those devices helps determine how well they bond with muscle, bone and other tissues.

It can also help with additive manufacturing, in which products are fabricated by 3D-printing them, layer upon layer — a technique that is transforming the electronics, automotive, aerospace and other industries. 3D printing often uses polymers, and researchers are constantly seeking new ones with better strength, flexibility, heat resistance and other properties.

The new measurement technique might also be used to optimize the polymer-based ultrathin films used in semiconductor manufacturing. As the components within computer chips get smaller and smaller — as Moore’s law predicts they will — the molecular orientations in those films become increasingly important.