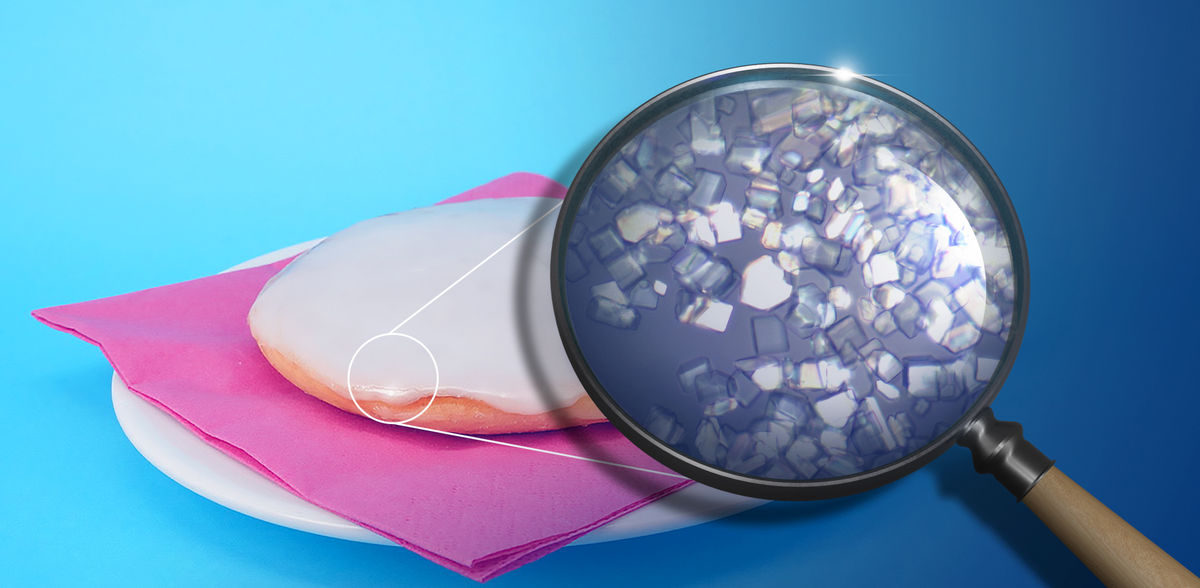

Fondant under the magnifying glass

New insights into the properties of sweet coating: The results could be used to optimize the industrial production process in the future

For many, the german sweet "Amerikaner" - a pastry with a sweet, whitish coating - is a childhood memory at the bakery. But there's a lot of physics and chemistry in the frosting. A team led by Thomas Vilgis at the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research, together with colleagues from the Technical University of Berlin, has now taken on the sweet glaze and gained deeper insights into its formation process. The results could be used to optimize the industrial production process of fondant in the future.

Sugar is the main ingredient - and you can taste it clearly: so-called "fondant" or melted fondant, which is used as a glaze on “Amerikanern” or petit fours - not to be confused with the roll-out fondant used for motif cakes.

The research team led by Thomas Vilgis of the MPI for Polymer Research from Kurt Kremer's department took a closer look at the microscopic properties of the model fondant, which contains only sugar and water, when it was produced and found unexpected behavior in terms of its viscosity. However, their findings could be relevant to even more processes in the food industry, such as the production of reduced-sugar glazes.

Fondant is made by mixing sugar with water. By heating it to near boiling point, even more sugar can be dissolved in it than is the case at room temperature. If the mixture is then cooled quickly, a so-called "supersaturated" sugar solution is obtained. This has dissolved more sugar than is normally possible at this temperature. As a result, if this viscous syrup is stirred quickly, microscopic sugar crystals form in it - the result is fondant.

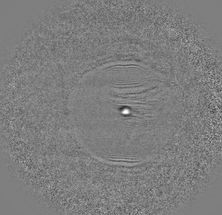

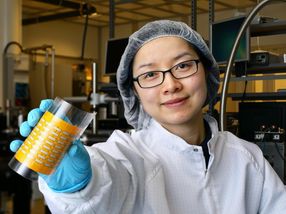

Vilgis' team has now recreated this manufacturing process in the laboratory using a laboratory mixer. This high-tech mixer is able to measure the viscosity with high precision during kneading. At the same time, they took samples at various times during the kneading process to examine them under a microscope and thus correlate them with the viscosity.

In doing so, they found that the mixture initially becomes highly viscous during crystallization before reaching its less viscous final state.

"We saw in the microscope that at the time of crystallization, quite large sugar crystals also form initially, in the range of 40-50 micrometers," said Thomas Vilgis. "Thus, these microcrystals have a size that one would perceive the fondant as slightly grainy on the tongue."

If one now stirs further, the viscosity decreases again and the crystals become smaller. "You can think of it as the larger crystals rubbing against each other. But the further you stir, the smaller fragments they break down into," explains Hannah Hartge, first author of the paper and a doctoral student in Vilgis group.

Only when the point of maximum viscosity is passed the fondant can be used as a creamy, sweet and shiny coating.

The researchers conducted the experiment depending on various process parameters such as temperature or sugar content: "Our work shows the interplay of crystallization rates and process parameters. This allows us to predict structure and function," Hartge says. "Until now, food systems like fondants have hardly been the focus of scientific research, especially physics."

Their results could make it possible to optimize process parameters in the production of fondant or even other, similar food systems, and thus produce the corresponding food faster and with higher energy efficiency.

The scientists were also able to describe the experiment using a simple theoretical model called "nucleation theory". "We were amazed that this nearly 100-year-old theory could describe the experiment very well - even though it was actually created for non-moving liquids, unlike our stirred fondant mass," Vilgis said. The reason for this, the researchers say, is that the movement of the sugar molecules is much slower compared to the kneading motion, and thus the sugar molecules can be considered "almost at rest."

For industrial production, the results published in the journal "Physics of Fluids" could help to optimize processes in fondant production.