Stretching single molecules allows precision studies of interacting electrons

With controlled stretching of molecules, Cornell researchers have demonstrated that single-molecule devices can serve as powerful new tools for fundamental science experiments. Their work has resulted in detailed tests of long-existing theories on how electrons interact at the nanoscale.

The work, led by professor of physics Dan Ralph, is published in the June 10 online edition of the journal Science. First author is J.J. Parks, a former graduate student in Ralph's lab.

The scientists studied particular cobalt-based molecules with so-called intrinsic spin – a quantized amount of angular momentum.

Theories first postulated in the 1980s predicted that molecular spin would alter the interaction between electrons in the molecule and conduction electrons surrounding it, and that this interaction would determine how easily electrons flow through the molecule. Before now, these theories had not been tested in detail because of the difficulties involved in making devices with controlled spins.

Understanding single-molecule electronics requires expertise in both chemistry and physics, and Cornell's team has specialists in both.

"People know about high-spin molecules, but no one has been able to bring together the chemistry and physics to make controlled contact with these high-spin molecules," Ralph said.

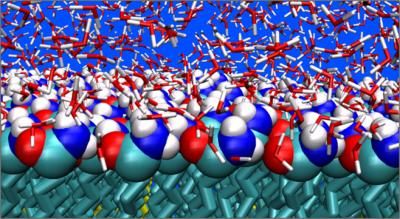

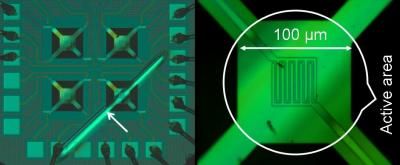

The researchers made their observations by stretching individual spin-containing molecules between two electrodes and analyzing their electrical properties. They watched electrons flow through the cobalt complex, cooled to extremely low temperatures, while slowly pulling on the ends to stretch it. At a particular point, it became more difficult to pass current through the molecule. The researchers had subtly changed the magnetic properties of the molecule by making it less symmetric.

After releasing the tension, the molecule returned to its original shape and began passing current more easily – thus showing the molecule had not been harmed. Measurements as a function of temperature, magnetic field and the extent of stretching gave the team new insights into exactly what is the influence of molecular spin on the electron interactions and electron flow.

The effects of high spin on the electrical properties of nanoscale devices were entirely theoretical issues before the Cornell work, Ralph said. By making devices containing individual high-spin molecules and using stretching to control the spin, the Cornell team proved that such devices can serve as a powerful laboratory for addressing these fundamental scientific questions.

Most read news

Other news from the department science

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.