Milestone single-biomolecule imaging technique may advance drug design

Knowing the detailed shape of biomolecules such as proteins is essential for biological studies and drug discovery. Modern structural biology relies on techniques such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy to discover the tiny structural details of biomolecules. All these methods, however, require averaging over a large number of molecules and thus structural details of an individual biomolecule are often lost.

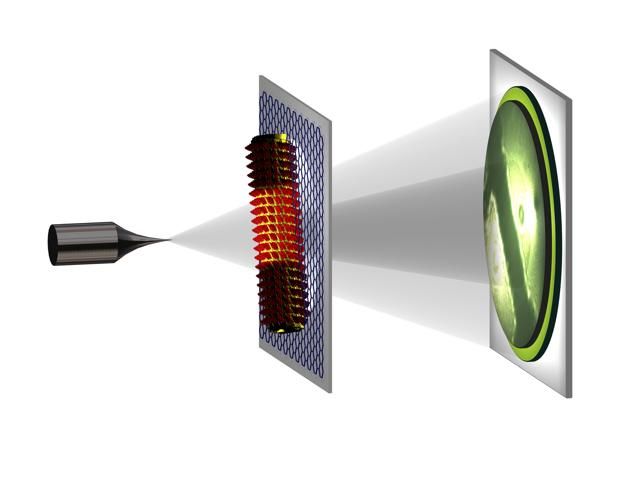

In low-energy electron holography an atomically sharp metal tip acts as source of a divergent beam of low-energy electrons. It represents a coherent spherical wave front with a wavelength of the order of 1 Angstrom. This beam impinges onto the object and part of the beam will be scattered by the object and a part will not be affected. At a distant detector we record the interference pattern arising from the interaction of these two beams. This interference pattern is called a hologram. The availability of the phase information encoded in the hologram enables an unambiguous recovery of the structure of the object.

T. Latychevskaia/University of Zurich, Switzerland

Now researchers from the University of Zurich, Switzerland have made a breakthrough by obtaining the first nanometer (one billionth of a meter) resolved image of individual tobacco mosaic virions, a rod-shaped RNA virus that infects a wide range of plants, especially tobacco. The work demonstrates the potential of low-energy electron holography as a non-destructive, single-particle imaging technique for structural biology.

"We've shown that by means of low-energy holography, it is possible to image individual tobacco mosaic virions deposited on ultraclean freestanding graphene," said Jean-Nicolas Longchamp, the primary author and a postdoctoral fellow of the Physics Department at the University of Zurich, Switzerland. "The virions are imaged with one nanometer resolution exhibiting details of the helical structure of the virus. Our technique would be the first non-destructive imaging tool for structural biology at the truly single molecule level."

Longchamp noted the technique would also open the door for "rational drug design," an inventive process of finding new medications based on the knowledge of a biological target. In the most basic sense, drug design searches for and chemically refines molecules that have some complementarity in shape and charge to some part of another molecule -- such as the binding site of a human protein involved in some physiological process that goes awry in a given disease. Better knowledge about the individual structures of those target proteins can help scientists develop more effective drugs.

"The low-energy electron holography has two major advantages over conventional microscopy. First, the technique doesn't employ any lenses, so the resolution won't be limited by lens aberration. Second, low-energy electrons are harmless to biomolecules," Longchamp said.

In many conventional techniques such as transmission electron microscopy, the possible resolution is limited by high-energy electrons' radiation damage to biological samples. Individual biomolecules are destroyed long before an image of high enough quality can be acquired. In other words, the low permissible electron dose in conventional microscopies is not sufficient to obtain high-resolution images from a single biomolecule.

In Longchamp's experiment, the tobacco mosaic virions were deposited on a freestanding, ultraclean graphene, an atomically thin layer of carbon atoms arranged in a honeycomb lattice. The graphene substrate is similar to a glass slide in optical microscopy, which is conductive, robust and transparent for low-energy electrons.

To obtain the high-resolution hologram, an atomically sharp, tungsten tip acts as a source of a divergent beam of highly coherent electrons. When the beam hits the sample, part of the beam is scattered and the other part is not affected. Using a distant detector on the other side of the sample, the researchers recorded the sample's high-resolution hologram, a pattern resulting from the interference of the two beams.

"This is the first time to directly observe the helical structure of the unstained tobacco mosaic virus at a single-particle level," Longchamp said. "Since low-energy electron holography is a method very sensitive to mechanical disturbance, the current nanometer resolution could be improved to angstrom (one ten billionth of a meter) or atomic resolution in the near future by improving the mechanical stability of the microscope."