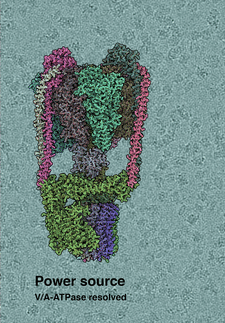

High-end microscopy reveals structure and function of crucial metabolic enzyme

The enzyme transhydrogenase plays a central role in regulating metabolic processes in animals and humans alike. Malfunction can lead to serious disorders. For the first time, structural biologists at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (IST Austria) have now visualized and analyzed the enzyme’s atomic structure with the support of the institute’s newly installed high-end cryo-electron microscope. The data presented in the journal Nature are relevant for the development of currently unavailable therapeutic options.

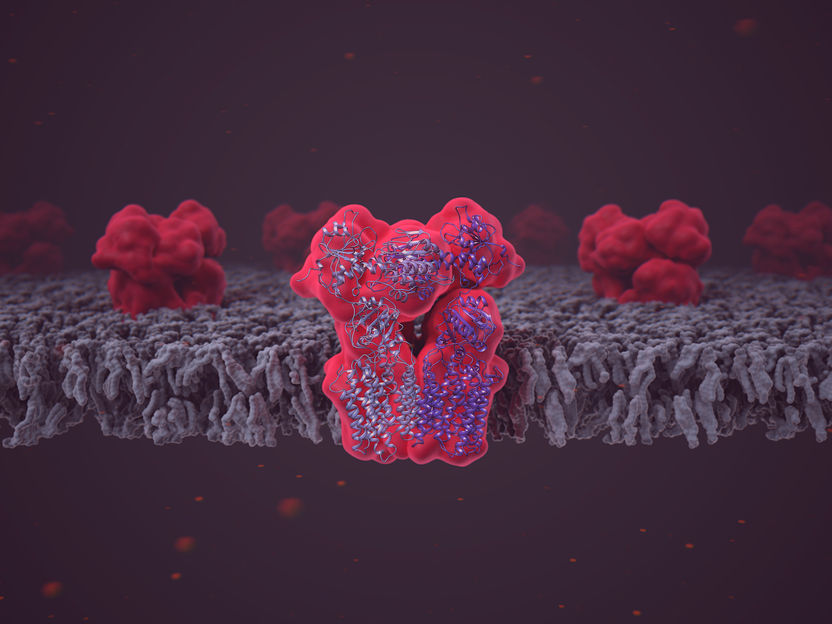

The enzyme transhydrogenase (NNT) embedded into the lipid bilayer of the mitochondrial membrane.

Martina Maritan

Within each cell, the power houses called mitochondria continuously break down molecules derived from food to generate energy as well as to produce new molecules that serve as building blocks of cells. Balancing these two opposing processes is accomplished by an enzyme called proton-translocating transhydrogenase or NNT (nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase). NNT sits in the mitochondria’s membrane and uses the electrochemical proton gradient generated by cellular respiration to provide the mitochondria with just the right amount of the co-enzyme NADPH, a vital metabolic precursor. The proper functioning of NNT is crucial for metabolic regulation in all animals including humans. However, the details of how NNT accomplishes the coordinated transfer of protons across the membrane and synthesis of NADPH have remained obscure due to the lack of knowledge about the enzyme’s atomic structure. Domen Kampjut, PhD student at IST Austria, and his supervisor and group leader Professor Leonid Sazanov have now for the first time visualized the molecule of mammalian NNT at a scale that allowed them to identify the structural principles of the enzyme’s channel gating—and thus to gain a deeper understanding of its functioning (and malfunctioning).

“Resolution revolution” at IST Austria

The atomic analysis of the enzyme NNT was only possible by taking advantage of state-of-the-art technology developments in cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), the so-called “resolution revolution”. Parts of the current study’s data were generated using a new cryo-electron microscope installed at IST Austria only in fall 2018 and are the first to be published using one of three new machines, the “300 kV FEI Titan Krios”, in Klosterneuburg. The cryo-EM analysis of NNT—which involved extensive time- and effort-consuming image processing and the support of the experts of the centrally organized and well-established Electron Microscopy Facility at IST Austria—delivered near atomic-resolution images of the molecule’s three different domains in various conformational states.

Opening the gate for protons—and new forms of medical treatment

With these images, the structural biologists could show how the domain that binds NADPH can open the proton channel to either side of the mitochondrial membrane. First author Domen Kampjut: “NNT has been studied for a few decades, but classical imaging methods such as X-ray crystallography have failed to give a detailed look into its structure because it is highly dynamic. Furthermore, membrane proteins like NNT are particularly challenging to study as they are fragile and difficult to purify in large amounts needed for crystallography. Thus, only with cryo-EM could we finally see clearly how the proton transfer works—and with this, find a missing piece of the puzzle on the way to understanding what to do if it does not work.”

Professor Leonid Sazanov adds: “These structures are particularly exciting because transhydrogenase performs an amazing volte-face by rotating an entire, quite large, NADPH-binding domain 180 degrees ‘up’ or ‘down’. This is, as far as we know, unique among studied enzyme mechanisms. However, such a rotation now makes complete sense in view of our proposed mechanism and it shows how nature can ‘creatively’ solve challenging tasks.”

The results are an important further step towards the development of novel therapies. For instance, the development of currently unavailable NNT inhibitors has great therapeutic potential with regard to metabolic dysfunctions including metabolic syndrome, and some cancers.